Design and Health World Congress

Report on Design & Health World Congress

Montreal Canada June 25-29 2003

Report © Lesley Greene

Introduction

This was the third world congress on Design & Health with a thematic emphasis on reducing stress through environmental design.

Design & Health is an international organisation, set up by Alan Dilani a Swedish architect with a special interest in health buildings. His international board consists of representatives from many Western, developed world countries, Italy, Canada, USA, Australia etc.

I attended the conference because

- I had helped prepare a paper presented by Maggie Redshaw, the environmental psychologist who evaluated the environmental impact of the new Bristol Children's Hospital on children, families and staff. The full report (90 pages) will be available from NHS Estates by the autumn [2003]

- I was interested to hear the latest international research findings on environment, arts, architecture and design on health to inform my continuing work in healing environments

There were 2 presenters from the UK, Maggie Redshaw and John Wells-Thorpe who presented his NHS funded study on mental health environments. Many presenters were from Canada - as host country - and there were many from USA and the Scandinavian countries.

Maggie Redshaw delivering her assessment of the new Bristol Children's Hospital to Congress June 2003

There were c300 participants, a disappointing number for the organisers who had received over 500 bookings until the SARS crisis.

The Lieutenant Governor of Quebec opened the conference. She spoke from her wheel chair, in English, in an extraordinarily open and passionate way about the need for good design as an essential component of healthcare. Clearly she spoke from the soul.

All the presentations were made in English; for one or two this presented problems during the discussion sessions.

Dilani and Professor Romano Del Nord highlighted the conference theme in the introductory presentations. Preventative medicine, seeking the causes of good health rather than illness, the shift to the 'wellness' factor, were key contemporary elements for a conference dealing with the stress reducing theme. Dilani took his own country as a paradigm. Sweden has a number of national goals for public health enshrined in government legislation. These include good eating habits and quality meals as an integral part of the healing process, access for all people to green areas for recreation and contemplation, including the sound of nature in our lives, opening up the hospital to the city as an integral part of the urban environment, creating places in hospitals for meeting and contemplation, recognising that natural light, colour and the arts add to our enjoyment of life and our ability to respond more quickly to treatment. Dilani quoted statistics to demonstrate that good health is 50% created by good working / home conditions, 20% caused by genetics, 20% created by access to leisure and recreation, and only 10% created by medical healthcare (so 70% of good health is as a result of our environment.) In the developed world mental and chronic disease is now replacing infectious disease as the major medical problem for society, raising the debate about the role of hospitals in a context of community-based care and preventative medicine.

Over the four days of the conference there were issues that in different ways kept emerging as 'keys' to unlocking the supportive healing environment. I will list them with references to the speakers whose research flagged their importance, plus particular points which I felt were important. The full papers will be published by Design & Health in the autumn of 2003 and can, I understand, then be visited on their website www.designandhealth.com

1. Patient centred healing featured in all presentations. 'Trust the patient' was a key message, to ensure that patients have an active role in their own treatment through provision of opportunities for access to information (through the web, a hospital library etc), have access to private areas for contemplation and quiet, and are able to have time and places for creative activities. The challenge for hospitals is to work with designers to bring about a 'motivating' environment that is comprehensible, interactive and allows personal choice.

2. The hospital and the city emerged as a major urban design issue. The hospital traditionally was regarded as a discrete entity. The hospital is seen now as a regeneration tool by city authorities, a key to 'healing' the ills of cities. This requires greater links between city and town authorities and their hospitals. Terry Montgomery (Canada) argued persuasively for much greater use of the urban master plan and an active relationship between local authority and hospital authority so that the hospital becomes an integral part of the planning for the city. Much hospital work and therefore space allocation is research based, more akin to the university model. He was strongly opposed to the green field site option for new hospitals, mainly on sustainability grounds. He went on to recommend 'planning for real' with neighbourhood communities and argued that this interconnection created greater understanding between communities and helped underpin city regeneration. Ragnhild Aslaksen's powerful presentation on the new Trondheim Hospital was an exemplar of this approach. Integrated art (Norway has an obligatory % for art scheme on all public buildings ø hospitals are public buildings) helped link the hospital to the city ø a series of light sculptures and sandblasted glass walls created positive way finding and a 'transparency' between city and hospital. 25% of this hospital is accessible public garden space. Marilyn Cintra ( Australia ) argued for participation of communities in place making through community arts development programmes - action research programmes. These programmes themselves became restorative at a community level.

Debate centred on the potential conflict between the use of hospital grounds or malls as public realm spaces and the need for secure and private, yet open, spaces for patients.

3. Sources of well being was dealt with in a variety of ways. Keeping the patients' mind active and encouraging lateral thinking on the part of the commissioning authorities to new design ideas was the focus of many speakers' research. Some used research from the business sector and workplace to illustrate the need for more creative thinking in hospital design; for example the company Skandia was quoted ø they found that poor ideas emerged from formal Boardroom meetings so they closed their Board rooms and enlarged their kitchen and cafeteria areas where discussion was not only freer but vertically possible, dissolving company hierarchies; new ideas in hospital design include building fitness suites and creating better access to information through integrating libraries in hospitals i.e. integrating preventative medicine and encouraging informed and participative patients.

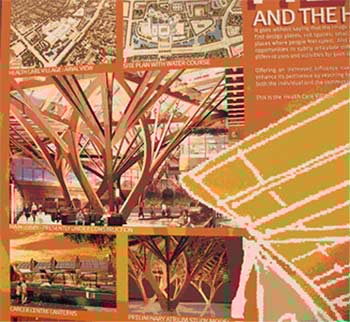

Others had worked specifically testing the impact of the arts on stress reduction. Leif Edvinson spoke about dancing having a huge impact on positive brain waves, creating a sort of 'brain gym'. Ann Langius, a nurse from Sweden presented a research paper on a study that showed patients exposed to music in and after surgery experiencing less pain and therefore requiring less morphine. Her message was clear that music is an inexpensive and non-invasive tool supporting surgery. She explained that theatre staff also performed surgery more effectively when music was played. There seemed to be a connection between musical rhythm and breathing which affected the alpha brain waves inducing relaxation. Susan Wesley's impressive "lullaby research" with children with behavioural difficulties demonstrated the significant impact of music on reduction of aggression. This research, which began in 1999, continues. An Australian study showed how painting and drawing had positive effects on patients with dementia. Others (Michael Moxam) talked of the need for textures in hospital ø the use of natural wood and stone rather than plastics, and the use of colours in appropriate ways (there was a study on colour perception and aging (Helle Wijk) and another on the positive impact of colour on way finding (Michael Moxam). The use of gardens featured in many presentations. The Peel Centre Credit Valley Hospital outside Toronto emulated natural woodland space by the design of an atrium, which was Gaudi-like in its use of tree shaped support structures in natural wood.

The Peel Centre Credit Valley Hospital outside Toronto

All were concerned that patients needed access to natural light and one presentation (Philip Mead USA ) included an engaging run through the history of light and health from the Greeks onward.

Some expressed concern about the availability of fresh food in hospitals. Rothman's work in the new teaching hospital in Mexico City stressed access to fresh, and, importantly, culturally appropriate food as an ethical issue in healthcare.

One small aspect of a larger environmental study by Michael Moxam showed that art had a more general importance for staff morale, than any perceived effect on patient recovery rates.

4. Gardens and light and the impact on patient care : Open spaces allowing natural light, and gardens, are commonly cited as stress reducing factors. This conference underlined, in a number of interesting presentations, how their impact on healing is well founded.

Two presentations focussed on the garden. The first by Susan Black argued the need to build landscape into architecture itself as an integral concept. She has planned gardens into wall structures, including internal water systems. Ulrika Stigsdatter presented workplace research from Malmo that demonstrated not all gardens were healing gardens. Research showed that any view can relieve some stress, but the greener and more natural (the 'granny's garden') the garden was, the more restorative effect it had, and, if, in addition, there was access to the garden, then that had an even more stress relieving impact on users. She used a Swedish word 'trivsel' which means pleasure, comfort and well being all in one. This was the specific word used to define the research objective in terms of healing.

A key presentation by Philip Mead detailed the many different positive aspects of natural light and access to an outdoor environment. He had explored Circadian rhythms and diurnal variations, the need for vitamin D variants and UV-B light (affecting heart and cell growth regulation re cancer) and the impact of serotonin, all of which are only accessible outdoors. He condemned all fluorescent lights. He proposed that a healing environment was only possible if hospitals included a variety of accessible outdoor spaces adjacent to patients' rooms ø these could include small sunspaces, even open windows helped. He claimed that any outdoor space, even if the view was limited, was better than no access at all to fresh air. Rothman's new teaching hospital in Mexico City faced south and had sun holes in the roof to access maximum natural light. These kinds of recommendations were repeated in other research done by Michael Moxam on acute care recovery rates where there was positive evidence of good responses to natural light.

There was evidence from the floor in debates about these issues that accessibility to garden or courtyard spaces is crucial as it also supports patient choice (Clare Cooper "Healing Landscapes").

5. The designers and their place in the system: designers are healers in partnership with the hospital and need to acknowledge the transformative qualities of their work. ÒThe environment is part of the treatmentÓ (John Wells-Thorpe). Artists need to be part of those design and planning teams (Maggie Redshaw on Bristol Children's Hospital and others). The work of the design profession is vulnerable in a value management system which recognises engineering and technologies and is subject to increasingly intensive risk assessments (i.e. the open window debate) . Moreover the design profession often fails to sustain the argument for those values which are Ôrisky' i.e. spaces with natural light, spaces for art, breathing walls, gardens etc., in the hard cost assessments of buildings. The task of the designer is in part to ensure that the humanistic design principle is embodied in the Project Mission statement from the beginning and that those values are shared and signed up to. Debate centred on the roles of hospitals boards and governments. In the USA , accreditation for hospitals was changed in 2001 to include access to nature, art, light and music as part of the Ôhuman dignityÔ concept (Elaine Sims). In Sweden the government is developing guidelines for healing environments (see introduction).

The questions from the floor throughout the whole four days challenged the relationship between what the speakers said they were doing and what they actually did. In part this came from a somewhat unnecessary Ôcommercial' thrust behind some of the conference presentations. Some would speak about integrating art and then show a slide of a rather poor painting hung in a corridor. Similarly there were a surprising number of examples of slides of (to me) extremely unfriendly architecture presented as 'patient friendly'.

One potentially interesting academic assessment of the standard North American atrium form as a function of private versus socialised healthcare, came to no conclusions. Was it the end of the research or did they not wish to embarrass representatives of large architectural companies responsible for many major Canadian hospitals who were at the conference?

In response to certain presentations, delegates from the floor spoke with conviction of design elements like gardens and art as being absolutely essential components in healthcare, particularly in certain specialist areas i.e. those dealing with the elderly, with children, and chronically sick patients especially those with cancer. These presentations included, for example, the Trilliam Health Centre, Canada. This specialist breast cancer clinic included a large dedicated exhibition space devoted to the work of mainly women artists. They had commissioned beautifully designed hospital gowns (rather than Ôgreen sacks') to reflect the dignity of women undergoing treatment. The Dornbecker Children's Hospital in Oregon included children's art throughout the hospital. The work was all donated by a patron so was not wholly integrated but was still interesting and well sited in well-designed spaces. All the waiting areas in the Dornbecker have children's libraries with beautifully designed bookshelves used as room dividers. The Bristol Children's Hospital's integrated colour scheme by a 'lead' artist was supported by an independent environmental assessment which found that the colours, brightness, respect for children through artwork hung at child height for instance, and Ômodern-ness', were hugely appreciated by patients and staff. The new teaching hospital in Mexico City has its own unique fabric designs for curtains, bedspreads, gowns etc. A study of patients in a burns unit in Washington State found that a virtual reality sequence of images from the Arctic produced goose pimples on unaffected parts of the skin, helping to reduce the pain of the burned areas, clear evidence of images changing our sensory perceptions.

Conclusion

This conference presented some well researched evidence that an airy, well designed and enhanced environment (through art, texture, planting etc) has significant impact on the morale of staff, on the perceptions of patients about the quality of care (Redshaw and others), in many cases reducing lengths of stay (Wells-Thorpe), and moreover can be an important and non invasive tool supporting actual medical treatment (music viz Wesley, Nilsson and others). Quality projects emerge as a result of teams working together with shared values. Another clear message is that independent evaluation is essential so that art is used appropriately in relation to healing needs; art for healing needs good friends and good evidence in relation to financial scrutiny.

There is an increasingly urgent argument about the role of the hospital in the city; issues of regeneration pit against patient security and the 'care in the community' debate.

There is always a question as to who pays for research and quality. The PFI process in the UK is a cost /time driven project. PFI consortia may genuinely support integrating the arts into their building programmes. However, in the end, to win the bid on cost, they will focus on achieving a satisfactory technical building, with long-term low maintenance implications for them. The sums included for art (and green public spaces) are likely to be low, and likely to be reliant on external fund raising.

As a result I have some questions: Has the Arts Council anticipated the potential demand on its resources from the PFI building programme? Recent NHS guides stress the ability of the arts to fundraise from external sources. Where are those external sources? Close on 100 new hospitals will be built over the next 10 years. Most of the commissioning Trusts will request art in their FITN. The Arts Council and key arts & health charities will be inundated with funding applications. Has the Arts Council set guidelines including what is expected as a minimum of the PFI sector or the commissioning Trusts? Or will they just give a few small grants to the biggest PFI bidders, or those in urban centres, or those who happen to be working with NHS Trusts which already have arts programmes (or not) or will it be first come first served? Will the sheer scale of new hospital arts applications impact negatively on applications from other areas of public art in any given region or community?

The biggest commissioning opportunity in the UK is already rolling and the Arts Council (save one or two regional exceptions) seems curiously quiet. Perhaps conversations have been held with the DCMS? Perhaps the Arts Council did ask the NHS to recommend a 'percent for art' as part of the PFI programme?

The PFI building programme is a one-off national opportunity to include more people in more parts of the country in the arts, to introduce more artists and art forms and participation in the arts than at any other time.

The Arts Council must be there to help promote and resource that opportunity, and undertake ongoing evaluation with NHS partners of the impact. Otherwise the biggest hospital building programme in Europe will happen with some art & some participation from artists dependent on energetic individuals or Trusts, but the opportunity to add significant artistic value, and evaluate the impact of art will be lost - apart from some isolated examples. Furthermore the partnership potential from an international commercial sector will not have been fully explored for the huge financial boost it could have given the arts and artists in this country.

© Copyright Lesley Greene, 2003