The Effect of Healthcare Architecture and Art on Medical Outcomes

Arts Council England Architecture Week Event

25 June 2003

Introduction and Welcome

Richard Burton: Good evening everybody and welcome to this Event ¯ this Architecture Week Event, organised by the Arts Council, the RIBA and in this case, by NHS Estates. My name is Richard Burton and I think I span roughly all three institutions and I think that's why I'm talking to you now. I would like to thank Marjorie Allthorpe-Guyton who's the Director of Visuals Arts at the Arts Council, who's sitting right in the front here, for the kind of enthusiasm that she showed when we first discussed this possibility. She really just picked it up immediately as one of the key issues for the future. I'd like to thank Claire Pollock, who is an organiser and has been an organiser of architectural matters at the Arts Council for many years and was there when I was involved, and finally I'd like to thank Philippa Barr who is Marjorie's assistant whose dedication has been remarkable. I want to introduce Sir Patrick Bateson, Professor. He is a Senior Fellow here; he is the Professor of Ethology and that is, the biological study of behaviour, at the University of Cambridge. He's also Provost of Kings College Cambridge since '88 and at a personal level he and I have been thinking about this matter one must say for maybe fifteen years and it's been those wonderful notes that I pick up from Patrick saying, this or that which have been a great inspiration for me. So without more ado I'd like to leave Patrick to introduce the speaker.

Sir Patrick Bateson: Thank you, Richard. When we started, Richard and I, talking about these things it was because we'd both been stimulated by the work of Roger Ulrich and it's marvellous to have him here because he really got us going. Well you've got statistics in your pack anyway about him. He got his first three Degrees at Ann Arbor, Michigan and then was recruited by a notoriously ruthless university, Texas A&M, who go for the best in the world and I can tell you not only is Roger the best in the world, he is a pioneer in his field and he has done more than anybody else to try to help people to design things in such a way that when people go into hospitals, which are inherently stressful, the environment reduces the stress. Roger, welcome, we're very glad to have you here and I'll give it to you so I can watch your slides.

Presentation by Roger Ulrich

Introduction

Thank you very much indeed. I am greatly honoured to be here this evening. The United Kingdom, with the increase in funding for the National Health Services, is on the threshold of a vast expansion in healthcare building construction. I hope that what I have to say this evening will be of interest not only to architects or designers, but also artists and medical professionals, or anyone with an interest in healthcare. I hope my comments will prove useful to at least some of you in thinking about the coming healthcare building boom - a wave of construction that will directly affect the lives of nearly every person in the United Kingdom for at least a few generations. It is very important to get it right.

Let me begin not with scientific research data but with an image. Imagine you are a patient who has been diagnosed with cancer. As you look at this slide of a huge hospital in northern Europe, imagine you have been dropped off in the vast parking area, or have just parked your car. In your worried distracted state you must try to find your way into this enormous and forbidding concrete building for a difficult procedure. But you are assailed by a hospital building of a general type that was built by the hundreds internationally from after World War II until recently, buildings that were functionally efficient, effective from the standpoint of supporting modern medical science and technology, and performed somewhat adequately in reducing infection risk. Such buildings are now sharply criticized, however, because patients and families find them starkly institutional, even brutal, and completely unsuited emotionally to their needs. As you take your imaginary walk from the car you will be in a distracted, even traumatised frame of mind, yet you need to navigate to the entrance. If you manage to find the entrance and then undergo the medical procedure, you will be put in a patient room with a window view that either looks at a concrete wall or has another room window looking directly into yours. When another patient is looking at you through the window, of course your privacy is invaded and you close the blinds. This happens to be a hospital in Scandinavia , but it could any one of a great many hospitals like it in the UK, or on the Continent or in the States.

Despite the negative public image of many existing healthcare buildings, my somewhat optimistic premise this evening is that the design of healthcare environments can be an effective medical intervention that can reliably improve outcomes. Accordingly, when informed by good evidence and done right, healthcare design warrants considerable priority. It follows, however, that healthcare design should be governed by standards that are somewhat similar to those for any other kind of medical treatment that can affect patient health, such as drugs or surgical procedures. As with medicine generally, if architectural design and the arts can affect outcomes, then the first principle should be "do no harm." And like medicine generally, design should insofar as possible be evidence-based or informed. Why? Because there is growing evidence that while well-designed buildings do improve outcomes, there is also accumulating evidence that poorly designed facilities, and such buildings are innumerable in Britain, the United States, Europe and Asia, worsen outcomes and substantially increase the cost of healthcare.

My objectives this evening are to review briefly the research to date on the effects of healthcare architecture and art on outcomes, and show examples of evidence-based design. The amount of sound research is limited, however, and there are many important questions for which directly relevant research is lacking. For these gap areas I will describe a research grounded design theory that suggests general directions for design solutions. I will conclude by examining the economic or business case for basing healthcare design on evidence.

First, a key term should be defined, "health outcome." Outcomes are measures of a patient's condition or progress, or indicate healthcare quality. Outcomes include clinical indicators such as the length of stay in the hospital and the number of drugs required for pain. Also, there are more subjective patient, staff and family based outcomes, for example, ratings of patient satisfaction with quality of care, or staff satisfaction with the healthcare workplace. Another very important category of medical outcomes relates to medical errors and patient safety. Finally, there are economic outcomes such as the cost of care or the expense attributable to staff turnover.

What is evidence-based design?

A second important concept that needs defining is "evidence-based design." The paramount goal of evidence-based design is to create healthcare environments that improve outcomes - ranging from clinical or medical outcomes such as pain or length of stay, to patient satisfaction, waiting times and safety indicators such as medical error rates, to staff outcomes such as turnover and retention, and economic outcomes. Healthcare architect/scholar Kirk Hamilton has written that evidence-based design refers both to a process for creating buildings that is informed by the best available evidence, and the product or built environment generated by such a process. As with evidence-based medicine, evidence-based design additionally entails an obligation to evaluate or study the healthcare environment after it has been constructed to assess the extent to which the performance meets intended goals. It is not enough to utilize a design process informed by evidence, to construct the healthcare environment, and then proclaim success with respect to achieving improved outcomes. Rather, data should be collected to enable an evidence-based evaluation of the extent to which the new environment actually is effective in improving, for example, patient satisfaction, reducing hospital acquired infections, and promoting efficiency and financial performance.

General State of Research Knowledge Concerning How Healthcare Design Affects Outcomes

What is the overall general status of scientific research concerning how architecture and art affect medical outcomes in healthcare environments? How much credible evidence is available for informing evidence-based design? The amount of research is limited but clearly growing. There are currently roughly 125 to 150 sound scientific studies that measure outcomes, use rigorous methods such as a randomised experimental design and have appeared in medical or other scientific journals. Five years ago The Center for Health Design, a not-for-profit organization based in California, commissioned John Hopkins Medical School researchers to undertake an objective assessment of the state of science, of sound knowledge, on the effects of architecture and art on medical outcomes. These were not architects or artists who reviewed the literature, of course; rather they were circumspect medical scientists. The investigators found tens of thousands of citations, the vast majority of which were based on intuition or only conjecture, and which often gave contradictory design prescriptions or "conclusions." They managed to uncover at the time, however, about 85 published studies that met criteria for scientific rigor. When the evaluators looked at the sub-set of the most stringent scientific studies they concluded that the success rate was about 75 percent. Success here means that the study found that a particular change in the architectural environment affected outcomes. That is an impressively high percent considering that the success rate for medical research overall is roughly 30-35 percent. The Johns Hopkins researchers concluded that while the amount of research is small by the standards of established medical fields, there is indeed evidence suggesting that environmental design does affect medical outcomes. Accordingly, this is an avenue that warrants greater attention. Recently the medical section of the American National Academy of Sciences, the Institute of Medicine , devoted part of a workshop to evidence-based design. So research about the effects of architecture on outcomes is beginning to come to the attention of leading medical scientists. Although the field is still at an early stage of development, something like a critical mass of findings is beginning to accumulate.

Research has shown that several outcomes are affected by changes in the healthcare physical environment. These outcomes include, among others, those listed below. The number of asterisks listed next to each outcome denotes my rather arbitrary ranking of the quality and amount of the research data available.

- Patient satisfaction with quality of care *****

- Patient emotional duress ***

- Pain reported and intake of pain drugs **

- Hospital acquired infections ****

- Sleep quality ***

- Injuries from falls **

- Length of hospital stay **

- Patient room transfers ****

- Medication errors **

- Quality of staff communication to patients ***

- Confidentiality of patient information ***

- Staff satisfaction *

- Staff turnover *

- Costs of care ****

Three years ago my colleagues and I at Texas A&M University co-sponsored a congress on design and health with the Karolinska Institute of Medicine in Stockholm. One of your countrymen, Dr. Colin Martin, observed in an article about the conference in The Lancet, that 'Evidence based design is poised to emulate evidence based medicine as a central tenet for healthcare in the 21st century.' Dr. Martin's optimism seems understandable against the background of the research summarized above showing links between health care design and outcomes. Well, the field is not there yet, but perhaps some day it will.

The following are examples of the many types of environmental or design properties that have been found by at least three or more studies to affect outcomes such as those listed above.

- Single/private patient rooms versus open wards

- Noise

- Air quality

- Presence/absence of a window; quality of the view

- Carpet versus linoleum flooring

- Design that fosters or provides control (includes privacy, choices, wayfinding)

- Environmental features that promote social support

- Design that fosters physical activity, mild exercise

- Nature, gardens, and art

I will be talking about some but not all of these in depth. In particular, I will discuss the influences of noise on outcomes, the effects on patients of single versus multi-bed hospital rooms, and the benefits for patients of well-designed gardens and appropriate art. But it should be noted that even design choices such as selecting linoleum versus carpeting have been found by research to have sometimes unexpected importance for outcomes. For example, a study in the United States examined outcomes of elderly patients who were spending about a month in a rehabilitation unit following, for example, hip replacement. The research question was whether it made any difference in outcomes if a patient was assigned to a room that had carpeting or vinyl composite flooring. The rooms were identical except for the variation in floor covering. After months of collecting data a surprising finding emerged concerning the effects of flooring on visitors. Persons who came to visit the patients with the glossy hard flooring stayed an average of eleven minutes in the room. By comparison, visitors to patients in carpeted rooms spent an average of 24 minutes. This raises the possibility that carpet in patient rooms might improve outcomes by heightening social support from visitors.

Keeping in mind that the overriding purpose is to create healthcare environments that improve outcomes, basic steps in evidence-based design include the following:

1. Using the best available evidence, design to increase patient safety - that is, to reduce medical errors, injuries from falls, hospital acquired infections

2. Eliminate or reduce environmental stressors in the healthcare environment such as noise that negatively affect outcomes

3. Design to ensure the presence of features and situations that research shows reduce patient stress and foster improved outcomes

Evidence-Based Design to Reduce Hospital Acquired Infections

As just noted, one important way that design can improved outcomes is by increasing patient safety. An example of a well established safety consideration is to create environments that reduce exposure to pathogens or infection. There is a worldwide problem with hospital-acquired infections, or nosocomial infections, and research has shown that design has major impacts through its effects on air quality and via the type of room created for patients. In brief, there is considerable evidence indicating that the better the air quality in the patient's room, the better are outcomes from the standpoint of hospital-acquired infections - especially for higher acuity patient categories. This argues strongly in favour of creating a greater number of patient rooms having, for example, ultraclean air from HEPA filters and negative air or ventilation pressure. The last, negative pressure, or pressure flowing into the patient's room, is key to reducing the spread of certain pathogens from one room to another.

Further, there is mounting evidence that single-bed patient rooms, in contrast to multi-bed rooms, have lower infection rates. When other factors known to affect infection rates are held constant, such as air quality and hand washing practices, several studies have found that patients in multi-bed rooms are more susceptible to cross infection from other patients. Put simply, having one or more roommates can be a significant risk factor for infection. This has been documented in several studies of nosocomial problems such as diarrhea, and for infections in different types of units ranging from critical care to general medical-surgical floors to neonatal intensive care. The growing concern for controlling infection from antibiotic resistant strains, together with the alarming recent experience with SARS, have underscored the importance of such considerations and added much momentum to a shift towards single-bed rooms.

Stress: A Major Problem in Healthcare Environments

Apart from improving outcomes by reducing pathogen exposure and increasing safety, another important perspective for understanding the effects of the designed environment - one that Professor Bateson alluded to in his opening comments - is that of stress and recovery from stress. The fact is only too well documented that stress is a pervasive problem in healthcare, that nearly all patients experience considerable stress and that many unfortunately experience acute stress. Stress is also a major problem for families of patients and for many healthcare employees. Reducing stress is an important medical goal because stress is both a negative health outcome in itself and it has a wide variety of detrimental emotional, physical and behavioral effects that worsen other outcomes.

The following lists a few examples of the many reasons why hospital patients and their families experience stress.

- Anxiety about the treatment, illness

- Pain

- Not knowing where to go or how to get there, in a large hospital

- Lack of information from staff

- Loss of privacy

- Having a room that is noisy, and prevents you from controlling the lights or temperature

- Loss of control

- I mpersonal attitude of staff, physicians; non-person treatment

Too often traditional healthcare buildings are themselves major sources of stress which add to the patient's heavy burden of stress from illness. I have proposed for some years that architects should use the best available evidence to help design healthcare buildings that greatly reduce the presence of stressors in the physical environment such as noise. Accordingly, a key step towards improving outcomes is to identify stressors in existing healthcare environments and insofar as possible get rid of them.

Noise: Example of a Stressor That Should Be Reduced

Let us focus now on one example of an environmental stressor in healthcare, noise. Much research has confirmed what our personal experience in hospitals tells us: hospitals and other healthcare buildings are noisy places. In fact, several studies in the US and UK have found that continuous background noise levels commonly are in the ranges of 65-80 decibels (dB), with peaks exceeding 85-90 dB. To put this in perspective, sound intensities of 85-90 dB are similar to those one experiences when walking next to a busy highway with trucks driving by. It is worth mentioning that the World Health Organisation issued guidelines several years ago recommending that continuous sound levels in patient rooms and treatment spaces should not exceed 35 dB. It appears that these guideline values are largely ignored by hospitals. Why are healthcare buildings so noisy?

First, noise sources in healthcare buildings are far too numerous, unnecessarily so, and many are loud. Examples are paging systems, alarms, and noises generated by roommates. Secondly, environmental surfaces - floors, walls, and ceilings - usually are hard and sound-reflecting not sound-absorbing, creating poor acoustic conditions. These acoustically poor surfaces cause noise to propagate or travel long distances, adversely affecting patients and staff over larger areas. Moreover, hard sound-reflecting surfaces are notorious for creating long reverberation times, that is, the time needed for a sound to drop 60 dB after the sound source has stopped. In addition to propagating sounds down corridors and into patient rooms, long reverberation times cause noises to linger and overlap, creating acoustic conditions that are known to be stressful and degrade speech intelligibility.

Several studies have found that noise worsens outcomes, for example, increasing blood pressure levels among patients in intensive care. It is no surprise that much evidence shows that noise causes patients to awaken and worsens their sleep quality. Until recently the methods used by researchers were rather insensitive in terms of detecting effects of noise on patients. Investigators would go onto a ward and ask as patient something like "Did you sleep well last night? Do you recall being wakened?" And it was indeed found that certain noise conditions caused sleep problems. Recently, much more sensitive sleep measures have been used. For example, Dr. Soren Berg at Lund University Hospital in Sweden recorded the brain electrical activity (EEG) of persons on consecutive nights in a hospital ward. These brain monitoring methods, which have been long used in sleep research, revealed that even low decibel levels - 38 to 40dB - were enough to consistently worsen sleep quality. An important finding in Berg's work was that persons were almost never consciously aware that they had been aroused from sleep. Nearly every time a low decibel noise occurred, and especially when poor acoustic conditions caused the sound to linger or reverberate in the air, the patient was aroused from deep sleep levels to shallow levels as indicated by changes in their brain electrical activity. Accordingly to established standards in sleep research, these findings indicated reduced sleep quality. Berg's findings have disturbing implications because most hospital wards have nighttime sound peaks far exceeding those of his study setting.

Recently I collaborated with researchers at the Karolinska Institute of Medicine in Stockholm, including Professor Tores Theorell, Vanja Blomkvist, Claire Eriksen, and two cardiologists, to investigate the influences of noise and poor versus good acoustics on outcomes for patients and staff in a coronary critical care unit (CCU) at a large medical center.

The patients were adults, the great majority of whom were diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction. They were assigned to single-bed rooms that were arrayed around a large central nurses' station. We concurrently studied thirty-six nurses in the unit who were specialists in cardiology. The environmental intervention in the study was to vary acoustic conditions from poor to good by periodically changing over a period of months the ceiling tiles throughout the CCU from sound-reflecting tiles (low performance) to sound-absorbing tiles (high performance) of similar appearance. All other environmental properties remained the same, including noise sources such as monitors and other equipment. Accordingly, the main acoustic property that varied was reverberation time (how long a sound lingered before extinguishing). Recall that longer reverberation times, compared to shorter times, are known to be stressful and interfere with speech comprehension.

When the sound-reflecting tiles were in place, the reverberation time averaged 0.8 second, a time commonly measured in many healthcare environments having sound-reflecting ceilings and floors. When the sound absorbing or higher performance ceiling tiles were in place, reverberation time dropped to 0.4 second. This shorter reverberation time potentially could be achieved or surpassed in quality in NHS hospitals. Although we in no way changed sound sources in the CCU, the sound-absorbing tiles (shorter reverberation time) substantially reduced the propagation of noises throughout the unit. When a noise was generated at the nurses' station, for example, it had lower decibel intensity by the time it travelled to patients' rooms when the sound-absorbing tiles were in place.

The study findings indicated that the good acoustics condition (sound-absorbing ceiling), compared to poor acoustics, had a number of positive effects on the nurses. (Two journal articles about the study are in press.) When the sound-absorbing tiles were installed, staff experienced lessened work demands and increased social support from fellow workers. This is good news because lessened work demands and higher workplace social support are known to be important for reducing turnover in nursing staff. Further, the staff reported that the quality of care they gave to patients was significantly better during the good acoustics condition compared to when the sound-reflecting ceiling was installed. Also, the nurses reported that they slept better at home when they experienced the good acoustics condition during their working hours. The improved staff sleep quality may be a carryover effect of less stress in the workplace. Lastly, the sound-absorbing ceiling condition substantially improved speech intelligibility. This is also noteworthy because of its implications for the possibility of reducing staff errors and thereby enhancing patient safety.

Concerning the patients in the CCU, when acoustic conditions were good they reported that nurses gave them better overall care. This was quite in agreement with what the staff reported. Also, blood pressure recordings were consistent with the interpretation that sympathetic nervous system activity in patients was lower when the sound-absorbing ceiling was in place. Reduced sympathetic activity indicates lower stress responding. Patients reported fewer sleep awakenings during the good acoustics condition. Also, there were indications that the incidence of re-hospitalization (within three months of discharge) was lower if patients had experienced the sound-absorbing rather than sound-reflecting ceiling during their stay in the CCU.

These findings, together with those from other recent studies not discussed, imply that noise is a more serious problem than previously thought in terms of adversely affecting outcomes. The message is clear: New healthcare buildings should be much quieter. Serious efforts should be made to remove or reduce noise sources such as paging systems and replace them with noiseless systems and equipment. High performance sound-absorbing ceilings should be installed extensively and sound-absorbing floor coverings used where possible.

Evidence-Based Design Guidelines for Reducing Stress

In addition to enhancing outcomes by increasing safety and eliminating stressors, evidence-based design also can improve outcomes by ensuring the presence of environmental features that are calming or stress reducing. Research in fields such as health psychology and environmental psychology suggests that there are at least four general design guidelines for creating environments that will likely be effective in reducing stress. More specifically, stress reduction and associated gains in other outcomes should be promoted by design that fosters:

- Social support

- Control (includes privacy, wayfinding, providing choices)

- Physical activity, movement, or mild exercise

- Access to nature, art, and other positive distractions

Evidence-Based Design Guideline: Foster Social Support

Social support refers to caring emotional support and tangible assistance that a person receives from others. Research indicates that patients who receive higher social support from their families or friends experience less stress and often have better outcomes. Examples of the wide variety of possible design approaches for increasing social support for patients include providing: comfortable waiting areas with movable seating; convenient overnight accommodations for family; single patient rooms with seating and a fold down bed for family; and attractive gardens close to wards with sitting areas that facilitate socializing.

Are single or multi-bed patient rooms better for social support?

Do patients sharing the same room provide each other with stress reducing social support? Advocates of multi-bed rooms often argue the answer is yes and that this represents an advantage of multiple occupancy over single-bed rooms. This belief, however, is based largely on a few interview studies of multi-bed ward patients who had little or no personal experience with private rooms. Directly contradicting this view are findings from several scientific studies showing that the presence of a roommate usually is a major source of stress. There are many exceptions to this, that is instances when the presence of a roommate has mainly positive effects. But in most cases roommates are linked to stressors, for example, having a roommate who is unfriendly, has too many visitors or is seriously ill. In light of the earlier discussion about negative effects of noise, it should be emphasized that research has demonstrated that noise is a much greater problem in multi-bed rooms than single rooms. Studies in acute care and intensive care units have shown that noises stemming from the presence of other patients (staff talking, patient sounds, equipment) often are the major cause of sleep loss.

Satisfaction with care in single versus multi-bed rooms

Most hospital patients in the United Kingdom traditionally have been cared for in multi-bed rooms. Professor Bryan Lawson and his associates recently studied patient preferences for single and multi-bed rooms in two NHS hospitals. They found that 54% of patients expressed a preference for multi-bed occupancy, but noted: "Of the patients who stayed in one type of accommodation, the great majority expressed a preference for it. Of the patients in multiple-bed spaces, 76% said they preferred them, while as many as 93% of the patients in single-bed spaces said they preferred them (Lawson and Phiri, 2003, p. 13)." This implies that the reason why a small majority of the patients preferred multi-bed rooms is that most - perhaps a great majority - had no previous experience with single rooms.

In the United States , roughly one-half of all patients have single rooms, the others are assigned mostly to two-bed rooms. A vast amount of data obtained from several million US patients over more than a ten-year period leave no doubt that the great majority of persons are more satisfied with the overall quality of their hospital care when they have a single/private room rather than a multi-bed room. This pattern of strong preference for single-bed rooms holds across all sizes of American hospitals, all major types of units and patient categories, and holds across socio-economic, gender and ethnic/racial groups. When Karmanos Cancer Center in Detroit converted older nursing units with small two-bed rooms to singles they achieved an immediate increase of 17% in satisfaction with care among their predominately African-American patients.

US patients who are older (more than 70 years) tend to be more accepting of having a roommate than younger patients (less than 50 years old). That is, older patients dislike multi-bed rooms but they dislike them less than younger patients. Multi-bed room are most disliked by women under the age of 40 years. When other factors that affect patient satisfaction are taken into account, the effect of being in a single room still increases satisfaction by several percentage points - upwards of nine to ten points - among younger female patients. It can be said categorically that US "baby boomers" (those born after World War II), especially women, strongly dislike multi-bed patient rooms.

One major reason why US patients are far more satisfied with quality of care in single rooms is that they find such rooms superior to multi-bed rooms with respect to social support. This finding runs directly counter to the belief that multi-bed rooms are better for social support. Both males and females judge single-bed rooms more favorably than multi-bed rooms from the standpoint of being with family and close friends. Family and close friends, not roommates or other comparative strangers, matter more to patients as sources of beneficial social support. Also, multi-bed rooms may often have space limitations and organizational characteristics that work against the presence of family members.

Another key reason why patients in singles are more satisfied is that they think that staff communicate better with them. It should be mentioned that the quality of staff communication accounts for about 20% of everything in patients' overall satisfaction with quality of care. Kaldenburg (1999) has proposed that when doctors and nurses are talking with patients in multi-bed rooms with roommates present, they automatically or unconsciously censor what they are saying out of respect for the person's privacy. It seems that when a patient is in a single room staff comments are more candid, informative and probably more emotionally supportive than when roommates are present. Good staff communication helps reduce patient anxiety, promotes better care at home after discharge and in other ways can improve outcomes. The superiority in communication of single rooms is so clear from the satisfaction data that as a researcher, one can track the same group of staff and observe they are rated as good communicators when caring for patients in single rooms, but are judged as poor communicators when caring for similar patients in multi-bed rooms. This underscores the very strong effect that ward architecture has on the quality of physician and nurse communication with the patient.

Healthcare administrators know it can be quite difficult to raise patient satisfaction with care by even two or three percentage points. Suppose that a hospital has mainly multi-bed rooms. What would it take in terms of a change in the hospital organization culture to increase patient satisfaction by as much as would be achieved by having single rooms? To achieve a roughly similar increase in satisfaction would require a major organizational shift such as transforming a culture where initially nurses and physicians were impersonal to patients, emotionally insensitive and avoided answering their questions. By changing to a culture where staff were emotionally sensitive and excelled at communicating and answering patients' questions, a roughly comparable increase in patient satisfaction might be achieved.

What are cost implications of some of the problems associated with multi-bed rooms? Evidence indicates that conflict or incompatibility among roommates occurs frequently and leads to costly patient room transfers. A study at Bronson Hospital in Michigan found that by moving from an older facility with two-bed rooms to a new building with mostly single rooms, at least $500,000 was saved annually in room transfer costs. Transfers can be very costly for patients in higher acuity categories. Clarian Hospital in Indianapolis saved at least $5 million per year by building a coronary intensive care unit with single acuity-adjustable rooms that reduced transfers by 90%.

Patient safety in single versus multi-bed rooms

Another very important advantage of single-bed rooms, reduced medication errors by staff, stems from the fact that single rooms lessen patient transfers. There is growing evidence that high rates of medication errors occur when patients are transferred from one room to another. Medication errors plague room transfers because communication discontinuities occur among staff, who usually change for a patient, and systems or computers change causing other errors. Even in some of America's best hospitals there appears to be at least a 70% chance of medication errors whenever a patient is transferred and the room changes. Single rooms lower errors by helping to reduce transfers compared to multi-bed rooms. When Clarian Hospital in Indianapolis changed from two-bed rooms in coronary intensive care to single acuity-adjustable rooms, the sharp reduction in room transfers was key in achieving a major reduction in medication errors of 67%.

Yet another advantage of single compared to multi-bed rooms is that they appear to reduce patient falls. Falls are very costly in human and monetary terms. Depending on the type of patient, the average cost of a fall in the United States can be several thousand dollars, and litigation often drives up this figure. Research has shown that falls mainly occur when patients get out of bed unassisted. Recently a study that videotaped patients in single and multi-bed rooms found that patients were less likely to get out of bed unassisted if they were in single-bed rooms that supported the presence of family. Because family members were there more often in single rooms to help patients, fall rates were lower than for similar patients assigned to two-bed rooms. Other architectural design features that reduce falls include decentralized nurses' stations that place staff closer to patient rooms and shorten response times to patient calls, and features such as grab bars and appropriate flooring. A recent U.S. study found that changing from two-bed rooms and centralized nursing stations to single-bed family-centred rooms and decentralized staff workstations reduced falls on a patient care floor by 75%.

Single-bed rooms may cost more initially to construct, but due to the substantial savings resulting from reduced infection rates, fewer falls, fewer medical errors and other advantages, single-bed rooms save money after year one of operation. And the quality of patient care increases. It is not surprising that new construction of American hospitals reflects a wholesale shift to single occupancy rooms.

Single Patient Family-Centred Adjustable-Acuity Room (Coronary Intensive Care)

Clarian Hospital, Indianapolis, Indiana

Evidence-Based Design Guideline: Foster Control and Privacy

In addition to the goals of increasing patient safety and social support, research suggests that healthcare architecture should also foster control in order to reduce stress and improve outcomes. Control refers to the patient's perceived or real ability to affect their surroundings and circumstances. Loss of control is a major problem for patients that generates much stress and negatively affects outcomes. Illness and hospitalisation erode control by impairing physical capabilities, involving painful procedures that cannot be avoided, or taking away control over eating and sleeping times. Traditionally healthcare architecture has aggravated the loss-of-control problem by depriving patients of visual privacy, control over lighting, forcing bedridden patients to stare at glaring ceiling lights, and creating wayfinding difficulties for patients and visitors.

Loss of control

View which a renal dialysis patient experiences for 3 to 3 hours a day, three days each week.

The positive news from research is that healthcare design that enhances control should tend to reduce stress and promote better outcomes. Examples of the many possible design approaches for enhancing control include providing: dimmers to enable patients to control room lighting; privacy in imaging areas; comfortable break rooms that give staff a sense they can escape briefly from workplace demands and stressors; and architectural design and signage that facilitate navigation in large healthcare buildings.

Good wayfinding fosters control

Prominent, easily located main entrance to Nortalje Hospital, Sweden

Large-scale artworks can make wayfinding easier

San Diego Children's Hospital

Chelsea and Westminster Hospital

Evidence-Based Design Guideline: Enable Physical Activity and Exercise

Physical activity is essential for most rehabilitation. Further, as with social support and control much research indicates that exercise is important for reducing stress and improving emotional well-being in patient populations. Physical activity or mild exercise can be especially effective for alleviating depression, a widespread problem among patients with chronic illness. Research provides a strong basis for proposing that healthcare design that enables or promotes exercise should improve psychological well-being and foster gains in other outcomes. Gardens can be exceptionally effective spaces for fostering physical activity if designed to facilitate patient accessibility and independence, and provided with features such as walking loops and seating. Another design approach to motivate exercise is to create corridor sequences that enable indoor walks in inclement weather. The corridors can be provided with pleasant window views of exterior gardens or nature areas, or opportunities to experience indoor art displays or atrium gardens.

Healthcare design to enable and motivate physical activity and rehabilitation

Rehabilitation garden at legacy Hospital, Portland, Oregon

Design Guideline: Incorporate Nature to Reduce Stress and Improve Outcomes

Positive distractions refer to a small set of environmental conditions or features that have been found by research to effectively reduce stress and improve emotional well-being. Distractions include certain types of music, companion animals such as dogs or cats, laughter or comedy, certain art, and especially nature. I will focus on the last two, nature and art. Let me note briefly that scientists increasingly believe or are proposing that because of millions of years of evolutionary experience in natural environments, modern humans may have a partly genetic predisposition to learn to like, pay attention to, and feel relaxed when they look at certain types of nature settings that were advantageous for early humans.

Research on nature

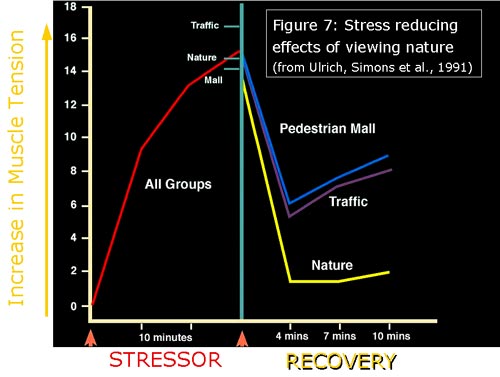

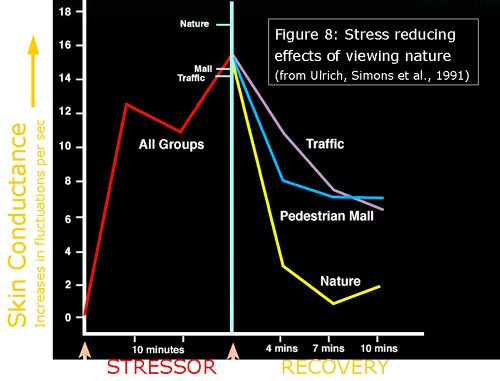

It is only in the last couple of decades that scientists have begun investigating seriously what happens when we look at nature and other visual surroundings. A key finding from several studies of patients and non-patient groups (such as university students) has been that simply looking at many types of nature substantially reduces stress with three to five minutes. The stress reducing or restorative effects of viewing nature or gardens are expressed in a constellation of positive emotional and physiological changes. Stressful or negative emotions such as fear or anger diminish while levels of pleasant feelings increase. Stress reduction in physiological systems is reflected, for increase, in blood pressure, heart activity, brain electrical activity and respiration. Figures 7-8 show findings from a study in which 120 nonpatients were first shown an unpleasant film that produced stress and then randomly assigned to a recovery period during which they viewed one of six different types of everyday outdoor environments. Some settings were dominated by nature (vegetation and/or water) whereas others were attractive built environments lacking nature. Figure 7 shows that muscle tension first increased during the stressor film but then declined substantially more when the persons viewed the nature settings compared to when they experienced attractive urban settings with people or traffic. Figure 8 displays findings from the same study for skin conductance, a measure that indicates sympathetic nervous system activity and can be said to reflect ³flight or fight² stress mobilization. As you can see, sympathetic nervous system activity goes up during the stressful film but then quickly and sharply drops when persons are viewing nature environments. Note that these stress recovery effects were produced by unspectacular nature settings such as a city park. An attractive English garden or a beautiful sea coast scene probably would have been more beneficial, but even undistinguished or common types of nature views can be effective in fostering recovery from stress.

Effects of viewing nature on recovery from stress: Figure 7

Effects of viewing nature on recovery from stress: Figure 8

It is worth reiterating that several studies done by different research teams have found that nature can effectively reduce stress. This reliability and convergence add scientific credibility to the finding. A limited number of studies have shown that even acutely stressed hospital patients can benefit significantly from a few minutes of viewing nature. Importantly, the stress reducing effects of nature appear to be hold to a surprisingly degree across diversely different socio-economic and cultural groups. In other words it appears that certain nature scenes reduce stress regardless, for example, if one is Chinese, American or Swedish, whether one lives in a rural area or large city, or has little education or an advanced university degree.

It was earlier emphasized that reducing stress in patients is important because stress negatively affects many health outcomes. By designing healthcare environments with nature to reduce stress and calm patients, it should therefore be possible to promote improvements in other outcomes. This is illustrated by the findings from a study of patients recovering from abdominal surgery who were assigned in a semi-random manner to rooms that were identical except for the window view--one-half of the patients had a window overlooking trees whereas the other half looked out on a brick wall (Ulrich, 1984). The groups of patients were similar in terms of factors that could affect recovery such as age, weight, and previous medical history. Those patients with the nature window view had better emotional well-being, suffered fewer minor postsurgical complications such as persistent headache or nausea, had shorter hospital stays and needed fewer doses of costly strong pain drugs.

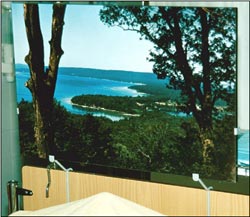

Another study at a Swedish hospital examined whether displaying nature pictures improved outcomes for patients following heart surgery (Ulrich, Lundén, and Eltinge, 1993). One hundred sixty patients in intensive care units were each assigned one of six pictures mounted at the foot of their bed: two types of representational nature scenes, two types of abstract pictures with colours comparable to the nature pictures (blues and greens), or two control conditions (either a white panel or no picture). Results showed that patients exposed to a landscape picture with water, trees and high visual depth suffered much less anxiety and pain than persons assigned to any of the other picture or control conditions. An unexpected finding was that an abstract picture dominated by straight-edged forms worsened outcomes more than if patients had no picture at all. A subset of patients had strongly negative reactions when looking at this abstract, necessitating its immediate removal.

Medical researchers at Johns Hopkins University recently studied the effects of an audio-visual nature intervention on patients undergoing a painful and unpleasant procedure, flexible bronchoscopy (Diette et al., 2003). Compared to patients randomly assigned to a control group, investigators found that patients assigned to view a nature scene and listen to nature sounds experienced significantly less pain.

Effects of nature and abstract pictures on heart surgery patients

Nature picture that reduced anxiety and pain in heart surgery patients (Ulrich, Lunden & Eltinge, 1992)

Abstract picture that increased anxiety in heart surgery patients (Ulrich, Lunden & Eltinge, 1992)

Gardens in healthcare environments

Evidence-based design can also be used to inform the creation of gardens that effectively reduce stress and promote gains in other outcomes. Apart from calming patients with nature views, well-designed gardens improve outcomes through other mechanisms such as physical activity and exercise (Figure 6), access to social support, and providing opportunities for positive escape and sense of control with respect to stressful clinical settings. There is limited evidence that garden views ameliorate stress effectively if they contain at least some of the following: verdant foliage, flowers, non-turbulent water features, a modicum of spatial openness, grassy spaces with scattered trees, compatible or harmonious nature sounds (birds, water, breezes), and visible wildlife (birds, squirrels) (Ulrich, 1999). In other words, qualities similar to those found in many traditional English gardens often are successful in calming and distracting patients. By contrast, there is suggestive evidence that gardens are ineffective in reducing stress when they contain predominantly hardscape or starkly built content (concrete, for example), intrusive urban or mechanical sounds (for example, traffic) and cigarette smoke. Whitehouse and her associates (2001) found that users of a children's hospital garden (patients, well siblings, parents, staff) disliked and avoided using areas having a high percentage of concrete or hardscape ground surface and/or starkly built or abstract features.

Evidence from a few studies has also shown that gardens and other nature in healthcare environments help to increase patient and family satisfaction with the overall quality of care. Other research suggests that hospital gardens increase staff satisfaction with the healthcare workplace and can be advantageous in hiring and retaining qualified personnel. These staff advantages assume major importance in light of the fact that healthcare staffing problems and shortages are a critical challenge facing healthcare systems in Europe and North America.

Gardens in healthcare environments

St Michael's Hospital, Texarkana, Texas

Atrium garden suited to location with long winters and snow

Bronson Hospital, Kalamazoo, Michigan

Using Art to Improve Outcomes

Limited but increasing evidence indicates that certain types of psychologically appropriate art consistently elicit positive emotional responses, can promote substantial recovery from stress and foster improvements in other outcomes such as pain. (for example the nature picture shown above). Research documenting these benefits is changing the view held by some that healthcare artwork is a "nice to have" embellishment or luxury. Evidence increasingly supports the position that emotionally appropriate art selected according to evidence-based guidelines imparts an important environmental dimension to patient care that improves outcomes (Ulrich and Gilpin, 2003). A growing number of healthcare administrators accordingly consider art as necessary for improving outcomes and quality of care -- a "must have" in hospitals rather than an embellishment.

Although emotionally appropriate art improves outcomes, there is also evidence that inappropriate art styles or image subject matter can increase stress and worsen other outcomes (for example the abstract picture shown above). These findings strongly support the conclusion that art selection for healthcare environments should be evidence-based (Ulrich and Gilpin, 2003). A related point is that the overriding criterion for healthcare art must be whether it improves patient outcomes, not whether it receives praise from art critics or approaches museum standards for quality (Ulrich, 1991). Even critically acclaimed artwork can be deemed "bad" if evidence indicates it produces negative reactions in many patients or worsens outcomes. Art varies enormously in subject matter and style and much art is emotionally challenging or provocative. Accordingly, we should not expect that all art would be suitable for high-stress healthcare spaces.

What art styles and types of subject matter do people prefer? Is preference highly individual - "in the eye of the beholder" - or are there patterns and similarities across different persons? Much research has shown that the great majority of adults (upwards of 85%-90%) in Europe , North America and Asia prefer representational art depicting nature. Further, a considerable majority of adults internationally like art that evokes positive feelings - "art that makes me happy" or is "relaxing to look at." There is also similarity across diverse cultures in terms of widespread dislike for abstract art. Echoing these findings, research on adult hospital patients has shown that a great majority prefer realistic nature art but dislike abstract art and especially emotionally challenging or provocative works (Carpman and Grant, 1993). Findings from studies of small groups of former patients who rated an extremely diverse collection of 676 paintings at a large urban hospital found that both African Americans and whites rated representational nature art as very appropriate for patient spaces. These included paintings of natural landscapes and rural areas, and images of gardens with flowers. Blacks and whites also deemed as highly appropriate for patient rooms figurative paintings that depicted people with positive facial expressions or caring gestures. Additionally, paintings of persons at leisure in gardens or other nature settings rated high in appropriateness and preference.

Examples of paintings which African Americans and Whites rated as highly appropriate for patient rooms

Example of art judged highly appropriate for patient rooms by both African Americans and Whites (Hathorn and Ulrich, 2001)

Both African Americans and White preferred figurative art showing persons in relaxed situations in nature (Hathorn and Ulrich, 2001)

In contrast to the great majority of the general public, studies confirm that many artists and persons seriously interested in art react positively to abstract and emotionally challenging images (this includes me). But there is growing evidence that such art content and styles can increase stress and worsen outcomes in many patients. A theoretical perspective proposed by psychologists, emotional congruence theory, is helpful for understanding these negative effects. In essence, emotional congruence theory holds that persons' feelings or emotions bias their perceptions of environmental surroundings in ways that match their feelings. The theory predicts in healthcare situations that the negative emotions experienced by many patients (fear, anger, sadness) should dispose them to perceive certain art styles and subject matter in emotionally equivalent negative stressful ways. Patients who are acutely stressed should be especially vulnerable to reacting negatively when art is abstract or ambiguous and can be readily interpreted in very different ways. Therefore emotional congruence theory implies that caution should be used when considering abstract art for patient spaces where stress is a problem. A safer approach is to select artwork with unambiguously positive subject matter that resists negative interpretation even by acutely stressed individuals.

The pitfalls of displaying abstract ambiguous art in healthcare environments are revealed by a study of psychiatric patients in a Swedish hospital. The ward was extensively furnished with a diverse collection of wall-mounted paintings and prints. Several patients in interviews expressed strongly negative reactions to certain abstract artworks in which the content could be perceived in multiple ways. The same patients reported having positive feelings and associations with respect to nature scenes. Earlier I described a study of heart surgery patients wherein persons assigned an abstract picture had worse outcomes than patients with no picture at all.

Here in London, Dr. Rosalie Staricoff and her associates administered a questionnaire to several hundred patients, visitors and staff at Chelsea Westminster Hospital to evaluate the arts program that includes paintings, sculpture and live musical performances. Findings showed that patients, visitors and staff responded quite positively to the visual art collection as a whole, reporting that the paintings and sculpture helped distract them from their worries and lessen stress. An interesting finding was that patients rated live musical performances as more effective than visual art in distracting them from worries and medical problems. My understanding is that this important arts/health research project will generate additional articles in the future about the effects of art on outcomes.

Example of abstract art which elicited negative reactions from psychiatric patients

Example of representational landscape art to which psychiatric patients responded positively

Implications: The Economic Case for Better Healthcare Architecture

One way to bring together the different strands of research discussed is to create a hypothetical but realistic scenario of a new hospital designed in accord with state-of-the-art knowledge. Fortunately, a distinguished business professor, Dr. Leonard Berry, who is my colleague at Texas A&M University, has recently developed just such a scenario and used it as the basis for a detailed economic or business analysis of the consequences of evidence-based design (Berry et al., 2004, in press). Berry and his associates create a hypothetical 300-bed US hospital called ³Fable² that incorporates a comprehensive array of evidence-based upgrades and design innovations. These include, among others, large single rooms designed to support family presence, oversized windows looking out at nature, HEPA filters to help ensure high air quality, decentralized nursing stations, several well-designed gardens, art throughout, and excellent support and break spaces for staff. But these upgrades add 5.3 percent or about $12 million, to Fable's already large initial construction cost. That is a substantial amount of additional money which in a real world situation could cause some accountants, hospital trustees or civil servants to make gasping sounds.

Professor Berry and his associates then set out a detailed analysis of estimated savings (cost reductions) and revenue gains conservatively attributable to the evidence-based design upgrades. The savings were calculated for estimated improvements in outcomes such as reduced patient falls, reduced room transfers, lower rates for hospital-acquired infections and lessened employee turnover. Estimates of cost savings were based on data from published scientific studies and on research carried out by several US hospitals participating in the 'Pebble Project' sponsored by The Centre for Health Design (Berry et al., 2004, in press). The Pebble Project is a research collaboration of progressive hospitals each committed to conducting a multi-year study to evaluate the effects of a new facility's designed environment on outcomes and costs of care.

Importantly, the authors conclude that the estimated savings and revenue gains for year one only of Fable's operation total approximately $11.5 million. It can be seen therefore that the savings and revenue increases linked to the evidence-based design upgrades nearly equal or offset the $12 million in added initial construction costs. After year one the financial impact of the upgrades is all positive, and the savings and revenue gains can be expected to recur annually over the decades of Fable's operation. Put simply, the message from the analysis is that evidence-based health care design makes compelling economic sense. It would be economically irrational not to spend more initially for upgrades and thereby in the long term incur substantially higher costs and reduce quality of care. The costs associated with the operation of a hospital and delivery of healthcare over a period of several years often are ten times or more greater than the initial capital costs.

Finally, I would like to offer respectfully some concluding thoughts as a person from across the Pond. Insofar as I understand the current healthcare situation in the UK , it would appear that most NHS Trusts could not build Fable Hospital. A major reason is that Fable Hospital would fail the test of the 'public comparator' standards, which seem not to reflect the most recent research knowledge regarding the effects of building design on outcomes. A related problem is that the current NHS building procurement process might place too much emphasis on reducing initial capital or construction costs, and perhaps not enough on creating buildings that reduce long-term operation costs and improve medical outcomes. Again, the centre of gravity of costs is clearly in long-term operation and healthcare delivery costs, not initial building costs. If an orientation to reducing near-term costs results in new healthcare buildings that are not up-to-date in terms of research knowledge, or not designed to be as effective as possible, there will negative effects on care quality and costs that could multiply intolerably over the long term. The public sector comparator standards should be re-evaluated and if necessary updated to reflect current research knowledge. I would like to challenge respectfully healthcare administrators to adjust the building procurement process to make Fable Hospital possible in the UK. It is in everyone's best interests for healthcare authorities and architects to utilize the best possible evidence to create the most effective possible healthcare buildings.

Thank you very much for your attention this evening.

PANEL SESSION

Richard Burton: Roger has described this Evidence Based Design and I have to say that in England, on this side of the pond, we have done an enormous amount of work, inspired by him and also of course confirming what his findings are. He has in addition of course put us into a wonderful situation of the new work on sound and so on. As architects that's absolutely crucial stuff. But I want to emphasise that people like John Wells Thorpe, who actually rang us up to say he couldn't be here tonight because he's doing a similar presentation in Montreal and Brian Lawson from Sheffield have just produced a really outstanding report on the effect of the improved conditions in two hospitals and they confirm what Roger found so many years ago. For those buildings that have been improved you get in patient times reduced, you get the lower analgesics and so on. And tonight we have here on the platform evidence, if we need it that we have it here in this country, and on my left is Rosalia Staricoff who has been mentioned already who's done four years of work at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital on these issues. I really am very very delighted you're here Rosalia, that's marvellous. I've mentioned Pat already. Now on my right I have Richard Mazuch who's an architect and works in one of the leading architects firms in this country. He works with Nightingales and Mike is somewhere here, Nightingales who are doing a large amount of work in this country on major hospitals and it's very encouraging that he has Richard here to help with that. And then finally we have an artist, Marc Chaimowicz who's - he's very humble when we were talking about this but actually he's worked in a hospice and he's doing big murals on the ceiling and so on and he's been faced by these problems and I think this is a good panel. And what I'm suggesting that we do, and I hope you'll agree, we haven't got time for lots of questions now but what I've asked the panel to do is to spend a few minutes reacting to Roger's talk and I'm going to start with you Rosalia to ask your leading question and then Roger will quickly answer, if you can, and then we'll go on to the next member of the panel. And I hope in that way we will cover the main questions that you might have and then we can all go and have a drink. Rosalia.

Dr Rosalie Lelchuk Staricoff: Thank you. Well my reaction is very positive. I'm delighted to hear all the evidence based medicine and architectural aspects that Roger has explained, especially because we have conducted research during the last three years at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, on the 'Effects of the Visual and Performing Arts in Healthcare' and what is interesting is that not only is it confirming what Roger has said, but it is also taking another angle. In our case we are, as you all know, in the centre of the city and that means that we don't have the luxury of having extremely big spaces with nature around and that means that in order to achieve the medical outcomes we all want, we have to provide different types of elements. Susan Loppert, Director of Chelsea and Westminster Hospital Arts has pioneered the integration of art and music, live music, into the environment of health care. Our scientific evaluation has given the evidence of the benefits of introducing arts, visual and performing arts, in a health care environment, which can be translated into real outcomes from the point of view of medical improvements, enhancement in the quality of the service and the reduction of costs. And we have the evidence that has been very clearly demonstrated that a length of stay in hospital can be reduced, the amount of analgesics can be reduced, just because the presence of art, appropriate art. I quite agree with Roger. It cannot be any, but appropriate art, including abstract art in our experience, and live music, which is extremely important and it's better than recorded music. There are many more aspects that we could discuss, but I'm just giving some outlines because we have very few minutes to discuss the importance of design and the introduction and integration of the art into health care environment to achieve beneficial medical outcomes.

Burton: Would you like to ask him a question?

Rosalia: Certainly, yes. From the scientific point of view I would like to ask you something. I would like to know how do you conduct your research in terms of how do you select the patients for instance or how long have you been working with each group?

Ulrich: There is not a brief answer. I try to be scientific in carrying out research. Compared to many research topics, conducting rigorous scientific research on healthcare buildings can be difficult because it is done in a complex real setting not a laboratory, so it becomes quite a challenge to control or standardize factors or variables that might affect the findings. It is often important to control for variability across different patients, for example, in illness severity or acuity level. I think there are advantages to selecting patient diagnostic groups where the numbers are large and for whom treatment is rather consistent rather than extremely varied, making it easer to control for factors.

Controlling for factors can be especially difficult when researching large-scale environmental aspects such as the effects of room dimensions or the presence versus absence of windows. These types of architectural design conditions cannot be varied easily or inexpensively, and only rarely can be assigned randomly to patients. So it is often very challenging to do the more rigorous types of controlled experiments. Having said this, there are still many environmental properties which can be rather easily varied and even randomly assigned, such as types of art on the wall, room colour, whether or not the patient can control their room lighting, or whether the ceiling is sound reflecting or sound absorbing.

Burton: I'd like to turn to you Richard. A practising architect with all these problems in PFI. Away you go.

Richard Mazuch: There are many questions that I'd like to ask Roger certainly and I'm not quite sure where to stop, but I'd like to ask him, have you ever considered looking more specifically at individual patient groups? I think we briefly touched on this before, but in terms of after all a patient can vary from a neonate, a pre-term baby to cardiac patient, indeed a pregnant mother going through ultrasound who might not appreciate the water effect or indeed a mental health patient. So in terms of our own problems as architects we're rather like tailors, we're designing suits for our clients. So every time we climb into an orthoptic department, an orthopaedic department the bells that ring, we appreciate the sonic environment, the colours, a pre term baby will not see form but see colour, all of these sorts of issues and there are many and I know there's so much research to be done, but will you be looking at in the future specific groups or medical, surgical ward situations and that sort of thing? That comes from my own shop.

Ulrich: I know you have been long concerned in your work to design appropriately for the needs of particular patient categories. I think research strongly supports the importance of doing that. Designing a hospital garden that is relaxing, calming and easily viewable from patient windows is appropriate for patients who cannot get out of bed and are captives in their rooms. But if the patient has had surgery and should get up from bed and walk, and if the therapeutic goal is rehabilitation through physical activity, then a garden designed appropriately for that patient should be quite different. A much larger body of research is needed that is focused or tailored to particular patient groups.

Burton: It was encouraging when Rosalia was describing her work that she'd actually done a whole set of studies of different departments, so I think we're going to see that.

Marc: I think we need an exchange. We need to do some joined up thinking I think.

Burton: Yes. Marc I'm going to turn to you now.

Marc Chaimowicz: Thank you. I'd have liked to hear more from Rosalia about the procedure by which they acquired their relatively fine collection, but it's still and after thought because my concern I guess is that aside from your conclusion that aspirational buildings in the UK aren't possible anyway, beyond that, in terms of what seems to be quite sketchy in terms of the visual arts, I mean I found for example that image from one of your research teams which you'd kind of fabricated yourselves with a microscope, I mean it's just not serious, it's not rigorous, I don't see how you can postulate that as art let alone as so called abstract art. It's not abstract art. It's a fabricated visual image which you then compare with a sort of third rate landscape image which leads you to conclude that bad art is good for the patient, so where do we start?

Ulrich: Marc, I take your point about the first image. You are right that strictly speaking, perhaps I should not call that image abstract art. It was a visual stimulation generated consciously and deliberately to be a control or contrast to the nature scenes with respect to colours and so on. But following the same general reasoning one might argue that many works of abstract art likewise are images fabricated deliberately to suit a goal or theory. As for finding that pedestrian types of art often resonate very well with patients, that is what the research evidence shows. As I said in my presentation what matters decisively as the criterion for whether art is good is whether the art benefits patients. It is certainly possible for art to be great or critically acclaimed and at the same time be effective in improving medical outcomes. Some Monets probably would work very well, but a real Monet would cost far too much. If research identified a group of inexpensive paintings by undistinguished artists that consistently produced positive reaction in patients, how could one ethically defend denying the art to patients because certain artists or critics considered it undistinguished? Also, when selecting art for healthcare spaces where stress is a problem, it is not acceptable to display artwork- no matter how critically good the art - that produce positive responses, say, in 30% of patients, disinterest in 40%, and negative reactions in 30%. Again, for art to qualify as good in healthcare it should have positive effects on the vast majority of patients. Negative responses should occur only infrequently and be acceptably mild. Thirty percent negative reactions would be unacceptably high. The first ethical imperative in situations involving vulnerable patients must be "do no harm." The ethical responsibilities of artists working in healthcare become especially important when patients have no control over whether or not they view the art. For instance, when a bedridden patient cannot avoid looking at art mounted directly in their line of vision. Unlike a person who visits an art museum, the patient has no choice or control. But I seem to be detouring toward a general discussion of what is good art, and certainly that is beyond the scope of our time.

Marc: But it highlights a flaw which is aside from what is good art which I concede is a complex issues, I think it highlights the flaw in which it would seem that the principle is based on bringing in art at the last minute to kind of decorate the walls and it would seem that if artists are seriously to get engaged with people from your areas, well from the panel's area of expertise and from their life's commitment to this kind of work, then the artist should be not seen as an afterthought but equally brought in at the inset as an integral part of the design team and they could then work with the architect to help actually integrally as you do with the gardens. You actually seemingly have more time for gardeners than you do for artists at this point because the gardens seem to work very well, because they're presumably brought in at the origin of the design procedure.

Ulrich: I could not agree with you more that art should be considered from the outset in designing a healthcare building. Two of the best examples of designing hospital buildings systemically with art in mind are here in Britain - Chelsea Westminster and I believe also St Mary's on the Isle of Wight. In these buildings art seems to be an integral part of the whole environment.

Burton: And Steve Nicol is here who worked with me on St Mary's Isle of Wight and we worked together virtually from the beginning with Peter Senior who I don't think is here, but he was the kind of representative to the artists and we had a whole plan set up where art was integrated from the beginning. Well Pat, you've seen it and it works pretty well. Can I turn to you now?

Sir Patrick Bateson: Accountants are often accused of knowing the price of everything and the value of nothing and I suspect that politicians may like that because when it comes to the benefits being down the line they're not likely to be within the lifetime of the government, but in this case it seems they might well be within the lifetime of the government, so maybe you'll have some success actually in persuading people that it would really be worthwhile to actually think about the longer term benefits. But that's a kind of optimistic comment. The question was driven by a point you made in your talk about why humans should like lush verdant scenes and I get slightly sceptical when I hear rather open ended things, well it must reflect something about our evolutionary past. These are told as sort of Just So stories which are very difficult to test, but I think ¯ my thought is this. What would be the benefit to a person of having these kind of preferences over not having them? That would be the evolutionary question. I mean how would it benefit somebody to have this kind of references. Patently they do have these references but why do they have them, what would have been the design thing that drove it?

Ulrich: I am obligated to give a thoughtful answer when the question comes from one of the world's most eminent ethologists, and a senior member of the Royal Society. My answer reflects my perspective as a social scientist. Several researchers, including distinguished evolutionary biologists such as Edward O. Wilson and Gordon Orians, have addressed aspects of your question. I have also contributed to the literature. First, you are right, it would be extraordinarily difficult to test and verify any explanation. But I believe that what I am going to say is plausible and works well from the standpoint of fitting with the research evidence. My contention is that humans have a partly genetic predisposition to respond positively to certain types of nature settings. Pre-modern humans arguably acquired such a predisposition because it conveyed survival-related advantages. Flight-or-fight stress responding was absolutely essential for early humans for dealing with threats and demanding situations. But flight-or-flight responses also involve substantial costs. They exhaust energy and produce other negative effects such as elevated blood pressure, high levels of stress hormones, and reduced immune system function. A capacity to recuperate quickly from these negative effects would have enhanced survival chances for pre-modern humans in several ways, such as by recharging energy. Following a stressful experience, pre-modern humans would be disposed to seek out, spend time in, and recovery from stress in secure nature settings where food and water were readily available. Spatial openness, water and verdant vegetation and flowers would signal security and food. It follows from these arguments that evolution may have left a mark on modern humans in the form of a capacity for restorative responses to certain nature scenes. There should be no such disposition for built environments and materials such as concrete. This speculation implies that nature features--gardens, nature art - should be incorporated prominently in healthcare buildings to help mitigate stress.

Burton: Well I'd like now to turn to one subject which I think we're all interested in and that is what are we going to do next? There's a huge amount out there, it's beginning to develop, evidence based design is obviously on the way and it's on the way here and it's on the way in the States and we as designers, we as architects, are going to be able to use it and that's the great thing. But I want to turn to my colleague and say, have you come across some kind of burning need for the next step? Richard.

Richard Mazuch: I think it's basically joined up thinking and bonding. I mean the needs are clearly there in terms of the patients, the illnesses and our hospitals and so on. We have answers and I think I mentioned a while ago researching and talking to a lot of the universities and even with Roger and so on. It's a bit like finding an answer to a problem going to my father's garage which was extended four times and it's full of junk but I can promise you that if I have a problem, if I look hard enough it is there. But one day if we can actually sort out that garage that's extended four times and put everything in order and on a shelf we can actually use those tools to solve some of the problems we have in hospitals and de-stress them and so forth.

Burton : But meanwhile we can do a lot already, can't we?

Mazuch: In terms of bonding and workshops as indeed we had yesterday.

Burton: Marc, anything, nothing? We'll continue with your ideal, there's no doubt about that.