A conversation between the Artist / Architect collaboration Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley, and Curator Lindsay Hughes on 9 March 2007

Introduction

Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley collaborate on projects that explore the realm between art, architecture and urbanism. Their work is concerned with how architectural space is perceived and articulated by those inhabiting it. The collaboration both intervenes in an improvised way within the city and generates gallery-based work in response to it. Warren and Mosley actively investigate places on the point of change and examine aspirations for the built environment alongside realities. Their work has been exhibited in Europe and New York and published in the architectural and art press. Current projects include ‘How to Make Art in Paradise’ an initiative in response to a suburban area in the Thames Gateway with Neville Gabie and Tessa Fitzjohn, and a collaboration with writer Robin Wilson on ‘Planning for Utopia’, a project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council at the University of the West of England.

Background to the collaboration

Lindsay Hughes- Can you give some background to your collaboration?

Sophie Warren- We've informally been collaborating since 1998 providing feedback on each other’s work and that was more formalised in 2000 when we collaborated on a body of work in response to motorway environments.

Jonathan Mosley- As an architect I've got very different training to Sophie as an artist and I think our trainings in a way give us different perspectives on the collaboration and bring different skills and approaches to projects… I would say I’ve been trained to respond to a brief.

SW- In contrast, during my training I initiated my own briefs and developed them. By the way, I think it is important to say at this point in the conversation that we're not talking on behalf of any other collaboration, or artist, or architect … for instance, some artists do work to briefs and so our discussion is very specific to each of us and how we work together.

LH- I think it’s a really interesting point where different practices come together with very different methodologies, and through that collaboration find a half way point where the ideas come together. I don’t know whether you have a structural way of working ideas through. But with your work and with each of your practices there's an obvious way that the collaboration gels, even though there are very different methodologies. There's a respect of those methodologies...

SW- I think we perceive each other as two practitioners who have shared interests and some interests and processes that are different as well. We don’t need to stake out our different territories. That doesn’t really come into it.

How the collaboration works

JM- I feel that it's really important that we're both quite interested in how a collaboration… how working with a person from another discipline who has different methods brings in an unexpected quality to the work. Instead of pursuing a project and it being about the limits of your methods or approach or your knowledge and experience, by collaborating with someone, you might make a step within a project where you are outside the realm of your expertise and beyond the limits of your experience.

LH- How do you keep that fresh, though?

SW- I think we are always investing time into exploring new ways of working and experimenting, bringing those interests into the collaboration. For example, I’m interested in performance and live art so that particular language and methodology is pulled into the collaboration. We seem to bring in influences from outside our respective disciplines and this invigorates our process.

LH - So, are there points in a project where you feel that one of you needs to be leading it, or are the roles more even than that and quite fluid?

JM- I think that within certain projects one of us might take a lead. We're quite reticent about talking about identification of roles because we don’t want to necessarily identify who does what within the collaboration as it does change from project to project. I think what we do... is allow each other time to develop ideas or develop a bit of process within the project individually, but then the individual brings that to the collaboration and there's critical dialogue. I think that's also something that helps to keep the collaboration quite fresh.

SW- It gives you that objectivity doesn't it, which if you are both very immersed in every aspect, you lose. I don’t think the roles are so set out from the beginning, there is a lot of just muddling around and then some evaluation of who might be doing what and then even after that point there's a time of batting that idea or process between one another as well...it's about both of you trying to realise the potential of an idea, of the work, and questions to do with authorship become quite unimportant.

PLATFORM: The game board is the city. The game will take you on a journey though the city on which you will negotiate boundaries, the territories of private and public space, the occupied and uninhabited, the surveyed and the forgotten. The object of the game is to place a Platform as near to a map grid intersection point as possible. A Platform is a model of architectural structure that appears to have no marked identity. It is open to interpretation and use. There are 70 Platforms, 70 participants and 70 grid points spanning from the centre to the fringes of the city. Each individual action of positioning a Platform within the city is a small but significant rupture in a landscape we know as planned and prescribed in its use. Collectively the action of the participants will create a new and momentary geography of the city and map the diversity and the intrigue of our built environment.

‘Platform’ 2006. Participant’s image contribution for grid point F5. Photo - Andrew Collinson, Jonathan & Leila

‘Platform’ 2006. Photo – Sophie Warren & Jonathan Mosley

Elements of collaboration

LH- Do you think then those elements of collaboration are present in how you work with other people like artists, curators and participants of the projects… do you think there's a different collaboration there?

SW- Yes, I think so… A project like Platform for instance sets out a game which engages the public in part of it. I think there is an exchange with the public but I would only call it collaboration in as much as it is an exchange within a framework that we have set up, which gives the participant or passer-by a place for their own creativity...

LH- I felt when I participated in Platform I was collaborating or maybe contributing…maybe there’s an interesting difference between collaborating and contributing.

SW- In some ways there were different tiers to that project. We had started the first part of the narrative which was then taken up by the participant, and then they contributed their own stories and experiences of the journeys that they took. The idea of actually leaving the Platform at its grid point anticipated that another story would unfold from that action. The work was something we initiated that included other peoples’ responses… quite a few of the Platforms were adapted, they were painted and adorned with drawings.

JM- The participants also contributed a picture or a bit of text to the project...

SW- ... Or found objects...

LH- Actually, through participating in that work, it made me think how I should do this more often… go and explore other places in the city. We tend to get into a routine and go to parts of the city that we feel comfortable with. Platform took you out of that comfort zone and caused you to look again at the urban environment.

JM- That work is in some ways a reflection of our process because we do enjoy going on journeys that we haven't been on before. We find that it is part of our inspiration. In some ways it's about making those unfamiliar journeys and then responding to the places we encounter.

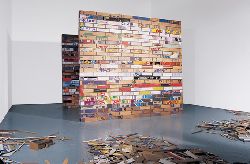

CLEARING - 728 UNITS: The work is comprised of three elements. The first element is an architectural structure which describes two near identical spaces separated by a shared wall. Discarded cardboard boxes of domestic products and consumables are adapted into building blocks for the structure, stacked to form walls of fragmented text, logos, lifestyle and brand imagery. The structure conjures up memories of rudimentary shelters, enclosures and cubicles. The spaces are full of choice and consumption and absent of it at the same time.

‘Clearing: 728 Units’ 2005. Photo – Sophie Warren & Jonathan Mosley

The second element is an expanse of remains which are created through the process of making cardboard bricks.The third element is a single building block which transcends its scale to evoke an isolated house set within a clearing at the edge of the remains.The scale of the domestic dwelling informs the scale both of the remains to suggest a vast and remaindered landscape and of the structure to suggest a Utopian mega-block.Through one process two landscapes are created which lie in tension with one another opening up new and unexpected narratives.

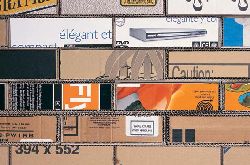

‘Clearing: 728 Units’ detail 2005. Photo – Sophie Warren & Jonathan Mosley<

Play and the built environment

JM- I think there are two strands to our practice. We create work which is interventional and placed out in the city, normally on the street. And then there's the gallery-based work.

LH- An intervention within an environment and a piece of work in a gallery are very different kind of experiences for the viewer. What is it about the nature of the objects in a gallery that add a different element to your work?

JM- A viewer’s experience of one of our gallery based installations is primarily spatial. I wouldn’t necessarily call them objects. We’re interested in creating and manipulating architectural space through structures that are experienced as both architectural models… and real scale constructions.

SW- Because the gallery based works are removed from the context of the street they can be seen more clearly or experienced as architectural propositions for the public realm… the works become like islands of thought… places of the imagination… and are set up to be quite easily manipulated containing that notion of a game again...

LH- Well, children play with small scale models like a small plastic animal in a model farm building. There seems to be this natural link between scale and play.

SW- It’s amazing to think how urban planners with master schemes for cities might move models of buildings around. However the notion of play seems removed from this activity unlike the way that children play around with a model of a farm building.

JM- But we want to release that possibility of play within people’s minds. The notion that planners and designers are manipulating big areas of the city and that they are thinking about them on that scale is fascinating. Allowing participants or the audience of one of our own installations to imagine themselves manipulating these small units, and those being representative of buildings and so various bits of city, I think is quite empowering. It’s a reaction to the fact we so readily accept what the built environment is in some ways and sometimes I don’t think there is the imagination at present of the full range of what is possible. It’s more about accepted norms. What we are trying to do is release possibilities in people’s minds for maybe other ways that you could form the built environment and other ways that you could inhabit it.

SW- … It’s because the built environment seems to have become quite fixed in its meaning.

Planning for utopia

LH- And the idea of a utopian way of living; for me that's really interesting. Whose idea of living is that? Is that a mass idea of living or is that just one person’s idea of living? I think that by opening up those possibilities, such as through me traipsing round trying to find my reference point in Platform, this gave me a new outlook on other possibilities. However, that sort of process is not included in the process of developing a new housing estate for example.

JM- If you then think about that point, that question, in relation to a lot of the work that we've done our understanding of utopia is almost in setting up a framework. The ideal is created by the way that individuals inhabit that framework. So you're not enforcing a complete vision on people. What you are doing is actually creating the opportunity for people to adapt their immediate environment and take ownership of public spaces.

SW- The works as architectural propositions set out to question those accepted norms we were speaking about… I think they are utopian in the way they are traces of resistance to existing systems.

JM- Absolutely. And the tension between the informal or adapted and the ordered within a master plan is something that we'd like to explore further. Many environments we experience in this country are very prescribed in their use; shopping in a retail area, living in a residential area. In one piece of work, Proposed Alterations to a City Plan we took the Local Plan of a city which designates uses to different zones of the city and we cut it up and spliced it together with a cardboard box that we had found within the city. It subverted the map and introduced the idea of the random into something very structured.

SW- And the notion of the left over…or something that’s found.

‘Proposed Alterations of a City Plan’ detail 2004. Photo – Sophie Warren & Jonathan Mosley

Exchange and collaboration

LH- What's the difference between exchange and collaboration?

SW- That's a good question because an exchange in a way can be a gift or an invitation to participate...

JM- I think in some ways the collaboration is the willingness of one party to understand the methods and approach of another party and to take some of those things on board. Whereas an exchange can be one party giving something to another person, the other person responding in their own way and giving something back. Collaboration is not about necessarily just swapping ideas, it is understanding the methods and the way that each individual develops ideas, their approach.

LH- When thinking about your work, and thinking about the collaborative process, I began to consider how your audience or participants could ‘collaborate’. But actually the notion of exchange is a lot more appropriate. The term collaboration seems to be over-used and has become something that we often talk about in relation to socially engaged work. We're starting to lose the true meaning of collaboration whereas more often than not it’s really an exchange of ideas.

SW- Platform was an invitation for people to take up or not, and the exchange lies in that invitation. I don’t think it was a true collaboration. Within the framework that we had set up however, we were very interested in how people responded to that invitation.

LH- In that respect a collaboration between, say a curator and an artist, or an architect and an artist there is often an exchange but there is rarely a collaboration.

SW- Yes… I think there's also an element of time within it. It takes time to form a collaboration ....I might be wrong - maybe some people can collaborate from the moment they begin.

JM- From our experience I think a collaboration evolves. A working partnership can start immediately.

LH- An exchange of ideas starts immediately and then from that the ideas form, start becoming fluid and then a collaboration may exist a little further down the line.

Acknowledging boundaries

JM- I think it's very much to do with boundaries and for a collaboration to work at its fullest potential there needs to be no boundaries..

SW- Or maybe it’s not denying that there are boundaries.

LH- But, acknowledging that there are boundaries.

SW- Yes, exactly. You can acknowledge them but it shouldn’t mean that you are not open to dissolving those boundaries or redefining them. That takes quite a lot of nurturing and you need to be in quite a safe place to do that. It is important that people feel that they can really propose ideas and lose their inhibitions to work creatively together. And in that way collaborations are quite particular to really make work.

JM- What’s helped us is a mutual respect of each other’s work, the dismantling of those boundaries slowly over time, and then a sort of willingness to explore each other’s methods and interests, but also keeping a space for the individual.

SW- I think that's another interesting question…how much you need to retain your creative autonomy, your independence within a collaboration. It is quite easy for that to be eroded away and you become dependent on the collaboration in order to realise anything and that independence is something that you positively strive to keep within the collaboration. It’s something you have to work at all the time as it seems to be essential in order to be able to contribute your…

LH- …individuality....

SW- …to do the work.

JM- It’s almost like there are three people involved in the collaboration. With us there's the individual Sophie, ...myself… and there's a third person which is ‘the collaboration’ and all those three people have to be working well together and keeping some space both for themselves and for each other.

LH- That’s incredibly interesting. And the tension and friction is a healthy element of that third person... just keeping the bit that agitates in a way… the third voice.

© Copyright Sophie Warren, Jonathan Mosley, Lindsay Hughes 2007.