Lighting projects

The Art of Illumination: What role do artists play in lighting our public realm?

The following paper was specifically commissioned for a PASW Regional Network Meeting held on May 1st 2007.

Listen to audio files of the Regional Network Meeting.

Introduction

At 7.30pm on 31 March, an organization called Earth Hour invited the inhabitants and businesses of Sydney, Australia, to turn off their lights for one hour. This they did, an action that recalls the recent cinema advert in which the music of harpist Joanna Newsom plays over pictures of the New York black-outs of three years ago, advertising mobile phones with the line: "Sometimes things need to switch off before people switch on."

Such events to illustrate the emergence of a romance of lightlessness, augmenting the increasingly vocal dark skies lobby, that for several years has been campaigning against the excessive and ineffectual use of light. Most notable among them is the Campaign for Dark Skies (CfDS), which has campaigned against the over-lighting of Britain since 1989, when it emerged from the British Astronomical Association (BAA) to spearhead its campaign against light pollution and 'sky glow'.

Since that time, the dark skies effort has gained wider interest, due to ecological concerns and also the conservationists' interest in preserving the wilderness: in this case, the wilderness of the night sky. Indeed, the movement compares with other quality of life initiatives, such as the 'Slow Food' movement. Just as that movement has Cittaslow - a network of 'slow' cities - the international Dark Sky movement has International Dark Sky Cities. The first one was inaugurated in 2001, Flagstaff in Arizona. [1]

Not too far from Flagstaff is Las Vegas, where the lights in the famous strip were turned off for Ronald Reagan's death in 2004, a move that was welcomed by the American Astronomical Society, and made particularly significant by its being in Las Vegas, a byword for light displays from neon to lasers. It was the seventh time that the lights of the famous strip have been turned off - previous occasions have been for the death of President Kennedy and for 9/11.

Architecture, environment and symbolism

So, lighting symbolises life and the lack of it symbolises death. In early animist societies the sun was revered as the giver of life, and therefore light became one of the most basic ways of expressing the world in symbolic terms. It is bound to be of interest to artists, as subject matter and medium, and in recent years, we have witnessed no less than a flourishing of light in the public realm.

The environmental concerns are necessary to articulate because, while public space light is more prevalent than ever, it is more vexatious than ever. In the last few years any matter involving the extraneous use of electric light elicits strong reactions. Light consumes energy, and therefore new lighting projects have to address criticism that they are potentially wasteful - or at worst, they

could be conceived as contributing to 'light pollution', which is illegal in the UK - the second worst light polluter in Europe after the Netherlands - since 2006.

Across the country architectural lighting has become commonplace. Landmark buildings such as churches are routinely lit at night. Lighting created by artists and designers is used by many local authorities in conjunction with public arts bodies to add value, drama and interest. From York Minster to Tyneside to the Thames, programmes of creative lighting have unveiled a new public art agenda. Among the various installations are Wavelength, the UK's largest ever neon sculpture, designed by artists Rob and Nick Carter on Victoria Street, London, and Bill Culbert's neon Coup de Foudre, in Canary Wharf. Nocturne, a light installation in Newcastle, has just opened, designed by artist Nayan Kulkarni.

Wavelength, Rob and Nick Carter, 2006

Commissioned by Land Securities

Cardinal Place, Victoria Street, London W1

Festivals and artist-designers

Festival-wise, Newcastle recently saw Glow, an outdoor light art exhibition curated by NVA; in 2005 there was Radiance light festival in Glasgow. Dazzle was a collective of winter festivals in the North East. Earlier this year saw the inauguration of Switched On London - claiming to be the city's first festival of light. Then there are the light festivals all over Europe - Lyon, Frankfurt, Berlin. A few weeks ago Hamburg had a maritime festival including a light show by light architect Gert Hof.

One could say that there's a minor boom in lighting festivals, and there is even an international body in LUCI (Lighting Urban Community International), which brings together a network of cities with a lighting strategy. All of these various initiatives - and the new technologies such as LED and low-energy bulbs - have given rise to a new commissioning policy of light.

So who are the people making the light work? The answer must be: a lot of different people. Roger Narboni, the author of 2004 book Lighting the Landscape: Art Design Technologies [2] says that "lighting designers have become a recognised profession" in the last two decades.

Equally, the new direction in public lighting has come from artists as well as from lighting designers, architects and engineers. It is a collective effort, and one that seems to have given rise to a more specialist kind of hybrid artist-designer, such as Jason Bruges, Chris Levine, Patrice Warrener and Raphael Daden. There are even socially conscious light artists, such as Veronika Valk from Estonia, who is aiming some light work to alleviate seasonal affective disorder, chiming with the notion that artificial light can alleviate depression and anti-social activity, as well as offer the public an enhanced sense of security.

People's Playground, Blackpool

Dune Flowers by Freestate with Chris Levine

Photo: Andy Atkinson; Model Making: Dante

People's Playground, Blackpool

The Northern Lights by Chris Levine with Freestate and LDA

Photo: Andy Atkinson; Model Making: Dante

The appeal of light

It is easy to see why light has become so popular. Much of the new lighting is dramatic, site-specific and time-based, turning environment into event. Indeed it captures the aspects of celebration associated with light, as well as its emotional and symbolic aspects. Not only is light is a highly effective and affordable medium, but it can work on several levels. It can offer sheer visual sensation; it can create different atmospheres, and it inexorably draws the eye.

For these reasons, light is used to make the point that an area is valued. From ex-industrial warehouses to waterside landscapes, lighting has become an essential visual cue of the regeneration process. What is more, lighting programmes are often temporary and reversible, making it easier to work with historic structures and planning requirements, while the technology

has developed and become more accessible.

Then there is the emotional appeal. Light is a symbol of change and hope, which means that as an artistic medium it often presents an accessible face to the wider public. Christmas lights and seaside illuminations, for instance, remain expressions of popular sentiment, part of a history of vernacular light in mass celebration.

Also, and very importantly, light works are seen as accessible. Simon Smith, officer for Glasgow's Radiance festival, said in the Times: "Light is very easily understood. It doesn't require any particular deep reading." In the same article Ekow Eshun, director of the ICA, said: "If the purpose is to create something that can unite people in a sense of joy and wonder, then light is one of the first places that you look", and the arts Ambassador for Birmingham, Nigel Edmondson cited the "perception of safety", adding that "in value-for-money terms, light so effective - what it can do to change environments and mood." [3]

Light as a religious symbol

As a religious symbol, light has long been used to present the ineffable with rays of light used in art from the earliest to indicate the presence of God, often emanating from a cloud. Light is, says the Dent Dictionary of Symbols in Christian Art, "The universal symbol in all major religious traditions of the unknowable power, beauty and mystery of God". The English medieval scholar Robert Grosseteste, who wrote De Luce, had light as the most direct corporeal manifestation of the divine, "the mediator between bodiless and bodily substance, at the same time spiritual body and embodied spirit'. Light, which could pass through glass without breaking it, was likened to the word of God, light of the Father, that had passed through the body of the virgin". [4]

Few might subscribe to those theological ideas in the modern context, but they seem to have passed down the centuries into the idea of the light sublime, most obviously in the work of James Turrell, probably the best known light artist working today. "We cannot touch or hold it, but we can see it, and with it, see our world. Light defines our physical, visual and mental experiences. It determines how we move and stirs our emotions," said the blurb for a recent exhibition in the US called The Magic of Light, presenting work by several artists including Turrell. "The concept of light is filled with a multitude of interpretations, ideas, and possibilities. It is a literal source of insight and a metaphorical image of revelation."

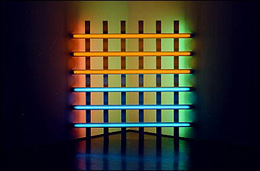

This is light as a representation of immanence, a theme suggested by the use of light sources in art from Caspar David Friedrich to Joseph Wright of Derby, Turner, Rothko and Dan Flavin, another 'light artist' whose oeuvre consists primarily of fluorescent light bulbs.

Dan Flavin, Untitled (For you, Leo, in long respect and admiration), 2, 1977

Turrell has been particularly influential in the public art sphere, and created many open-air environments that play with the figure-ground relationship of a light source, where light can suggest both solidity and absence. Supposedly, when Turrell showed one of his abstract illuminations at New York's Whitney Museum, several visitors mistook the light for a wall, leaned upon it and fell. Now, Turrell takes on many light projects, such as the Roman aqueduct in Nimes. [5]

Light as a marvel of technology

So, one could conclude that we are in the latest phase in the public perception of light, aided by a greater range of lighting technologies and new commissioning strategies, which are reinvigorating the sense of wonder.

When electricity first came to the cities of the UK and US in the 1880s, light was a source of fascination, partly because of its expense: a single light bulb cost half a day's wages and a kilowatt of electric power correspondingly pricey. The first public electricity supplies were in themselves noteworthy events, worthy of depiction, such as in an 1882 engraving from Harper's Magazine, of electric arc lighting in Madison Square, New York. Something about this early light magic recalls Martin Creed, whose Work No.227: The lights going on and off won the Turner Prize in 2001 - not a public favourite, but one that expressed a simple act of transformation.

Light was a marvel of technology, a theme developed in Charlotte and Peter Fiell's book for TASCHEN, 1000 Lights [6] in which the authors say that "...few human endeavours have had such a far-reaching influence on the development of civilisation as the invention of artificial light", and point out that just 100 years ago, "transforming night into day with the flick of a switch was hailed as nothing short of miraculous". Interestingly, Fiell alludes to the ecological dilemma by saying that the "development of artificial light has provided a vital means of independence from the rhythms of nature." That sense of discordance with the natural order brings us back to Las Vegas, where light is used to create an inability to tell between day and night, in order to keep people up and gambling. And already, fears were emerging about the new technology.

As Robert Louis Stevenson said about arc lights in the 1880s: "The word electricity now sounds the note of danger - a new kind of urban star now shines out nightly, horrible, unearthly, obnoxious... such a light as this should shine only on murders and public crime." It should also be noted that around this time of early public electricity - the 1880s - the visual arts began their experiments in fleeting retinal perception, most notably with the Impressionists, creating form through light and colour.

Light and modernism

Public light displays go further earlier than the emergence of electricity. St Peter's in Rome had exterior candle holders in 1547, and was described by Goethe - whose last words were famously 'More light' - as a 'fiery elevation'. Similarly, the wooden pagoda in St James Park had 10,000 decorative gas lights in the early 19th century. Of course, electricity presented an opportunity for the large 19th century international and world fairs - a new source of spectacle. Paris World Fair, for instance, saw illuminations placed on waterways. The Millennium Celebration's River of Light was an update of this era of light spectacle.

The early period of modernism, in visual arts and architecture, found the dynamic essence of light to be subject matter - as in Giacomo Balla's Street Lamp of 1909, where a lamp sends pulsating shards of light outwards. The phenomenon of rays, and light rays in particular, were explored in avant garde art movements of the time, most notably Rayonism, which moved the perception of light rays towards abstraction. [7]

Light became part of all that was dynamic and progressive. As the Futurist architect Antonio Sant'Elia, in his Manifesto of Futurist Architecture, said: "We have lost our predilection for the monumental, the heavy, the static, and we have enriched our sensibility with a taste for the light, the practical, the ephemeral and the swift." [8] Electric light suggested everything about what it was to be modern, a notion expressed in the 1920s, when many light festivals were held across Europe.

This appears to be a time when the concerns of the artistic avant garde and the creators of urban spectacle converged. Berlin im Licht in 1928, for instance, convened a committee of artists, architects and businessmen to develop illuminations: one plan was for the artist Naum Gabo to design lighting for Unter den Linden.

The 'architecture of the night'

Light gained credence as medium and subject of artistic enquiry. Theo van Doesburg of de Stijl called for a "lichtarketectur" - light architecture. Laszlo Moholy-Nagy experimented with light forms while at the Bauhaus, and Fernand Leger described projected light frescoes. "Spatial experience," said art critic Gyorgy Kepes, "is intrinsically connected with the experience of light", and in 1929 Form magazine asked in relation to light: "We might ask if our traditional understanding of form, based as it is on material values, might not be replaced by a new more comprehensive notion..."

So developed an interplay - perhaps sometimes even a tension - between the designers and creators of spectacle and the avant garde: one that continues to this day. In the pre-war years, notes writer Deitrich Neumann [9] many of the lighting designers had begun their careers at the theatre, and so had a dramatic mentality. Public light was firmly a part of showmanship - such as here with the Eiffel Tower - but was also part of artistic endeavour.

By 1930, notes Neumann, the term 'architecture of the night' was coined to suggest a growing interest in the nocturnal aesthetics of buildings. The early modernist architects - Erich Mendelson, Bruno Taut and Mies van der Rohe - carefully considered the night-time appearance of their works, considered to be something like a photographic negative. The pulsating essence of the city at night seemed particularly prevalent in the US, and something of that excitement is captured in Georgia O'Keefe's American Radiator - Night (1927).

Light and public sentiment

The use of light was to take a different turn in the monumental light-works of National Socialist party architect Albert Speer, whose most famous piece of public light-work, in 1934, was to surround the site of the Nuremberg parade grounds in 1934 with 150 anti-aircraft searchlights pointing into the air, an effect that was dubbed the "Cathedral of Light".

Despite its propaganda use, Speer's work has gone into the history of public light, and draws us into the current era, as the use of two sky-pointing light beams was offered as one of the potential memorials for Ground Zero. [10] It is not to be a permanent installation, but temporary twin pillars of light have been shone from the site on anniversaries of the event.

This is the emotional light of absence: the candle in the window, and the use of light as occasion for aspects of national sentiment, of mourning or triumph, as in 1945, when light beams converged above Los Angeles as a 'tribute to victory'. Interestingly, artist Hiro Yamagata hoped to commemorate the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan, destroyed by the Taliban regime, by projecting laser images onto the huge cliff where they once stood. [11]

New technologies

New technologies have offered new possibilities for public light art. The laser - first produced in 1960 - became an opportunity for a generation of artists, including specialists like Rockne Krebs, who contributed to the 1969 exhibition 'Laser Light - a New Visual Art' at Cincinatti Art Museum. He was the first to create an outdoor laser installations, such as Inclined Planes, in Pennsylvania, while artist Dani Karavan work showed 'Homage to Galileo', 1978, in Florence. [12]

They brought the searchlight idea further, showing how the laser had graphic sensibility, and paved the way to a new wave of audio-visual spectacle in the 1970s and 80s, from the musically responsive lasers of Paul Earls, to the work of Iannis Xenakis Diatope, seen outside the Pompidou Centre in 1978, and multifarious rock shows.

Still, light was being used to present modernity and develop opportunities presented by new technologies. For instance, Harriet Casdin-Silver's piece Centerbeam, 1977, which debuted at the art fair Kassel Documenta, used the new medium of holograms and later, was exhibited outside the Smithsonian's Air and Space museum.

The future

Now, the concerns for public lighting appear to be a greater interactivity, or the presence of a wider conceptual framework. A Buffalo Bayou lighting and public art master plan in Houston, Texas, to be finished next year, is an example of a sophisticated scheme expressing a 29 day lunar cycle in white and blue lighting by the architectural lighting firm L’Observatoire International and artist Stephen Korns. [13]

Buffalo Bayou project

Bridge lighting along the Sabine-to-Bagby Promenade

Photo by Elaine Mesker-Garcia

Then, here are the subtle gradations of Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall, LA, also done by the Gehry practice, and Highline, to be finished next year, by Diller, Scofidio + Renfro in New York, which traces an abandoned freight line, allowing for ' an intimate experience at night'.

So the lighting is becoming smarter, drawing from ideas that merge art and technology. This collaborative approach - and the new ecological considerations - should drive through a more disciplined lighting agenda.

As Roger Narboni says, 'the illumination of architectural and natural heritage sites has become more common without always adding a great deal of added value to the image of the town at night." It is time to move the world of 'lighting development master plans' from a monumental approach, with its bombast and excessive floodlighting, to what Narboni calls a 'proximity' approach, expressing the creation of 'ambiences', and 'nocturnal identity', with the social as important as the spectacle. Perhaps the current environmental concerns will aid this change, offering a challenge to the imagination of artists and designers in light, which will move the agenda forward once more.

References

1. See the International Dark-Sky Association:

2. Roger Narboni, Lighting the Landscape: Art, Design, Technologies Birkhauser 2004

3. The article is here:

http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/article632962.ece

4. As quoted in Colour and Culture, by John Gage, Thames and Hudson, 1993

5. One of the many explanations of Turrell's work can be found at : http://www.guggenheimcollection.org/site/artist_work_md_155_3.html

6. 1000 Lights: 1879 to 1959, Charlotte and Peter Fiell, Taschen 2006

7. For explanations of Futurism, Rayonism, see Tate's useful glossary at: http://www.tate.org.uk/collections/glossary

8. From Architecture of the Night: The Illuminated Building, by Dietrich Neumann (Prestel, 2002).

9. Sant'Elia's manifesto can be read at: http://artsaha.org/?page_id=79

10. See the book Imagining Ground Zero: http://www.amazon.com/Imagining-Ground-Zero-Unofficial-Architectural/dp/0847826570

11. See the project here: www.bamiyanlaser.org/en/exhi.html

12. From Art of the Electronic Age, Frank Popper, Thames and Hudson, 1993.

13. From Ultimate Lighting Design, teNeues, 2005. See further details of the project here:

http://www.buffalobayou.org/sabinebagby.html

© Oliver Bennett, May 2007. All rights reserved. Links updated October 2008.