An Artist's Perspective

Remember What Jack Said

Introductory Remarks

The current interest in artist/architect collaborations seems to date back to the late 1970s when architect Richard Hobbs invited artists into the design process for the Viewlands-Hoffman electrical substation in Seattle.

This was soon followed by the collaboration in 1983 between Cesar Pelli, Scott Burton and Siah Armajani on Battery Park, New York. In the UK, the first collaborative process was, probably, Tess Jaray's work on Centenary Square, in Birmingham, completed in 1990.

These early experiments in 'art as public space' required a closer fit between art and architecture, and this was achieved by artists collaborating with architects and, what Miwon Kwon [1] describes as, the other "members of the urban managerial class", ie. planners, urban designers, and city administrators.

The lessons learnt, from what is now over 25 years of collaborative practice, are complex. Not only is it still impossible to say what makes a successful collaboration, but the very contexts in which we might want to collaborate seem increasingly determined to stop us imagining a better world together.

Not every artist can do this sort of work

We were discussing this only the other day. Jack had been presenting his collaboration with Alice Adams on the Seattle metro project, and was now taking flak from a disgruntled artist in the audience. I couldn't guess how Jack was going to respond - what had seemed like a positive insight into collaboration had just been destroyed by 'pissed off' of Birmingham, or some other such place.

Well, Jack looked the guy in the eye and said, 'Not every artist can do this sort of work - and maybe you are one of them.' And that's when I understood how it works. Just because you are an artist doesn't mean you can collaborate. The collaboration, and the ability to collaborate, come first - and it doesn't matter much whether you are the artist, the architect, the client or the girl next door.

Katherine Clarke [2] got it right when she said, "Collaboration is the making of a relationship not an object... Although it sounds obvious to say it, collaboration is about difference, otherwise why bother. Acknowledging difference opens up a space to recognise what you didn't know, what you do know, and what you didn't know you knew; this is the substance of collaboration far more so than the material outcome that may or may not result."

Build the relationship first, then identify the differences, and then create the space.

Collaboration or Cooperation?

In most art and architecture collaborations, the relationship between architect and artist is usually defined by the division of the project into its component parts, ie. the building, the external works, the artwork, etc.. Theory describes this sort of relationship as cooperation (Roschelle & Teasley 1995) [3]:

"Cooperative work is accomplished by the division of labour among participants, as an activity where each person is responsible for a portion of the problem solving."

Collaboration is different. Collaboration is a "coordinated, synchronous activity that is the result of a continued attempt to construct and maintain a shared conception of a problem." Or, more simply, the "mutual engagement of participants in a coordinated effort to solve the problem together."

So if the project is divided, and we each work on a different component part, then we are cooperating and not collaborating.

If it is accepted, though, that we want a collaborative relationship ¯ ie. something more than simple cooperation, then we must attempt to build and maintain a collaborative approach.

Five Steps:

1. mutually agree to collaborate;

2. work collaboratively (site visits, meetings, drawings, discussions, e-mail exchange, etc.) to build a shared understanding of the project (the site, the vision, etc.);

3. work at understanding each other's differing abilities, knowledge and experiences;

4. establish coordinated mechanisms (meeting schedule, critical path, information exchange procedures, etc.) to support the collaboration;

5. agree a programme of higher level (principals/principles) sessions which enhance the shared understanding of the site and create an over-arching vision for the project. This may be about revealing opportunities and overcoming constraints. It might simply be about making drawings together.

These five steps can be understood, Bull & Brna 1997 [4], as a collaborative state based on a coordinated dialogue rooted in the belief that each participant can make a significant contribution to the project.

Echoes from a Collaboration (Dear David/Dear Larry)

Of course, beyond the five steps set out above, there is probably no blueprint for collaboration. Nothing can, or indeed should, be predictable in what is essentially a dynamic process. I've just been skimming through e-mails that, in many ways, illustrate something of the collaborative process - in this case a two year collaboration with an architect and other artists.

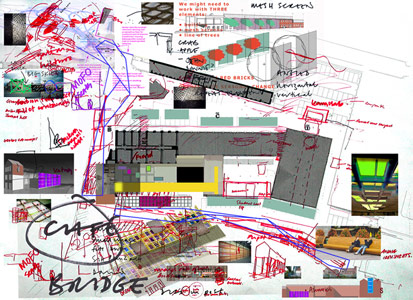

'Conversation Piece', Electric Wharf, Coventry

David Patten/Bryant Priest Newman Architects, 2003

Dear Larry

The important thing about the site visits is not so much what we look at (although that is important) or talk about (although that is also important) but how bits of looking and talking get spliced together to suggest new possibilities.

- this is a bit like Chuang-Tzu's "Thus their one thing together with their talk about the one thing makes two things. And their one thing together with their talk and my statement about it makes three things. And so it goes onŠ" And this sits at the heart of any successful collaboration ¯ simply, if you are not doing this then you are not collaborating.

Dear David

SORRY, I responded to previous e-mail without opening the attachment. Have now done so and really like the ideas and image!

- always read everything. Be thorough.

Dear Larry

Brilliant - I am with you.

- and good ideas come from both sides.

Dear David

Just to remind you we haven't received the CD with images referred to in salvaged materials schedule that you prepared - can you bring tomorrow please.

- don't forget to do what you promised! Again, be thorough.

Dear Larry

Well, I've spoken to both 'X' and 'Y' and I'm no wiser! Let's see what happens over the next few days, and if things aren't sorted we should discuss the situation on the 16th.

- things always go wrong. You can see it coming. There's nothing much you can do about it. Collaboration isn't a defensive shield.

Dear Larry

Bastards! Oh this is a mess!

- and, if they can, things do go wrong.

Dear David

Very interesting - I am humbled. Yes, I think it's a runner.

- sometimes it is good to surprise (but probably not necessary to humble) your collaborator.

Dear Larry

It could be something like this, but you've got a better sense of design!

- and sometimes you just have to come clean, and say you're not as good at something as the other person.

Dear David

We need to think quickly where we go from here.

- sometimes you get lost along the way, or a good idea is destroyed by the inevitable.

Dear Larry

This might be a useful drawing to take next week. It shows something of process and dialogue. It also says where we've been.

- collaboration is a bit like Thoreau's cabin [5], "I had three chairs in my house; one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society." That third chair is really important ¯ it defines the collaboration and allows the collaboration to interact beyond itself.

Dear Larry

It is only 9.30am and I already catch myself smoking two cigarettes simultaneously! I am concerned that in the rush to get the drawings done for Friday, we might forget some of the things we have explored over recent months. We need to grasp these things and make space for them to happen.

- collaboration doesn't, in itself, remove the usual stresses and challenges associated with getting the work done and delivering the outputs.

Of course the assumption is always that the collaboration is between one artist and one architect, when, in fact, other people get involved - including other architects and other artists. Sometimes this can be a negative - the thorn in the backside that needs to be dealt with so that you can sit down again and get on with removing the thorn in your foot. And sometimes it simply just works, enhancing the experience for everybody involved and increasing the possibility of something very special happening.

Dear Jane (from Charlie)

My relationship with the other people attached to the project has been one of open debate and free exchange of ideas, motives, needs and insights. This has been an exciting and informative process that has fed the work. My role fluctuates from observer, listener, researcher, advisor, idea juggler (my favourite), 'what if' scenario jockey, to producer of images that ultimately meet the brief at hand.

I have a particularly close working relationship with Larry and David. This has been mutually beneficial and informative as to how other thought patterns and needs are articulated and manifested into product. I have been constantly amazed at the cross readings of each other's practice and how this has moved into action via the collaborative process.

But beyond particular specialist function what has been most interesting is the evolution and revealing of a mutually shared idea of what this project might be or could become.

- collaboration is inclusive and not exclusive. Others need to come into the dynamic process to confirm, challenge and/or extend the possibilities. After all, the intention is not to have a cosy relationship but to produce the best work possible.

Capture the Imagination and inspire the people!

Within regeneration and place-making collaborations, the artist's sense of touch, rooted primarily in the 1:1 experience of painting or sculpture or craft, has allowed a different take on the possibilities for the social, perceptual and indigenous to influence what are essentially economic and marketing projects. How well we understand this as an important contribution will now be tested by new policy imperatives and funding programmes that may, because of their inherent conservatism, discourage the meaningful involvement of artists as legitimate collaborators. Maybe this won't be a bad thing.

Maybe it is time for artists to seek out more interesting collaborations in less commodified circumstances. Or maybe we stick with it if only to remind policy makers and funders that what constitutes public space should always be contested and constantly (re)negotiated.

How brave are you?

To some extent, Maurice Maguire and I set up pro/POSIT [6] out of frustration with the experience of collaborating with architects. This is not a criticism of anything or anybody, it is simply a recognition of the inherent historical and contextual flaws in the relationship between art and architecture. Despite the current emphasis on setting up artist and architect collaborations, nobody should believe it is possible to overcome the weight of history.

Although the relationship between art and architecture has always been enjoyably complex and reciprocal, it has also always been an unequal and, perhaps, unfair relationship. Architecture has defined and dominated the physical and psychological contexts in which art has been allowed to operate since, in Europe at least, Brunelleschi got his own back on Donatello.

It doesn't really matter how brave any of us think we are being in establishing or working in an artist/architect collaboration, we are still paying for those eggs Donatello dropped when he "acknowledged himself beaten" by the art and skill of Brunelleschi's crucified Christ [7], and the full-blooded collaboration between artist and architect - the very thing we all work for - remains, at best, elusive. And nothing will change this until somebody is brave enough to commit fully to the phrase 'artist-led project'. How brave are you?

Future Possibilities

Actually things have changed greatly since Viewlands-Hoffman in the late 1970s, and certainly much has changed since Jack Mackie stood up at the 'Context & Collaboration' conference in Birmingham in 1990 to present the Seattle metro project. Probably the biggest change has been, as Miwon Kwon has noted, in the shift of the collaborative focus away from "a physical location - grounded, fixed, actual - to a discursive vector - ungrounded, fluid, virtual."

It is too early to guess the impact this is going to have on 'art as space' collaborations, but, in the emerging voids left by the disappearing acts of both art and architecture, new possibilities for collaboration are beginning to appear:

"new tools and new professionals, people who can move between sectors and groups, weave agendas together, and find common aims without claiming power. Perhaps these people, of whom there should be more and more, could be what Blake called the Golden Builders of the cities." [8]

Concluding Remarks - The Don'ts

Okay, let's face it - you've come to this page looking for advice on collaboration, looking for the do's and don'ts. Hopefully I've already covered, or at least suggested, some of the do's. And I think I have said something of the contexts within which some collaborations tend to occur. So here are some don'ts.

- Don't come to me looking for a blueprint for collaboration, it doesn't exist. If you want to know about blueprints, read Calvino's 'Cities & The Sky 3' in Invisible Cities [9] ("We will show it to you as soon as the working day is over; we cannot interrupt our work now."). Otherwise, you are better off trusting to instinct and just getting on with it.

- Don't collaborate if you are a princess, prima donna, or shaman. It just won't work. You are the thorn in the backside. Remember what Jack said.

- Don't enter a forced marriage - it will end on the rocks. Fall in love first.

- Don't be exclusive or elitist - be open and generous.

- Don't forget Donatello's eggs - they are very important in all of this.

- Don't think of collaboration as anything special, it isn't. It is just a way of working. And when it works, it is the best way of working.

References

1. Kwon, Miwon. One Place After Another: Notes on Site Specificity, October 80 (Spring 1997).

2. Clarke, K. RSA Awards - Notes on Collaboration (undated).

3. Roschelle, J. & Teasley, S.D. The construction of shared knowledge in collaborative problem solving. In C. O'Malley (ed.). Computer Supported Collaborative Learning (1995).

4. Bull, S. & Brna, P. What Does Susan Know That Paul Doesn't? (And Vice Versa), in B. du Boulay & R. Mizoguchi (eds), Proceedings of International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, IOS Press, Amsterdam (1997).

5. Thoreau, Henry David. Walden and Civil Disobedience, Penguin Classics (1983).

6. pro/POSIT is the formal working partnership between David Patten and Maurice Maguire. Founded in Cambridge in 2001, pro/POSIT creates 'perfect moments' with other golden builders, and is currently collaborating with Bryant Priest Newman Architects on the design development of the Irish Quarter in Birmingham. Further information at www.proposit.co.uk

7. G. Vasari Lives of the Artists - A Selection translated by George Bull, Penguin (1987). "Thus, one day when Donato [Donatello] had finished a wooden crucifix (which was placed in S. Croce in Florence, under the scene where St. Francis raises the child, painted by Taddeo Gaddi), he wished to have Filippo's [Brunelleschi] opinion; but he repented, for Filippo said that he had put rustic on the cross. Donato then retorted, "Take some wood and make one yourself," as is related at length in his life. Filippo, who never lost his temper, however great the provocation, quietly worked on for several months until he had completed a wooden crucifix of the same size, of extraordinary excellence, and designed with great art and diligence. He then sent Donato to his house before him, quite ignorant of the fact that Filippo had made such a work, so that he broke an apron-full of eggs and things for their meal which he had with him, while Donato regarded the marvel with transport, noting the art and skill shown by Filippo in the legs, body and arms of the figure, the whole being so finely and harmoniously composed that Donato not only acknowledged himself beaten but proclaimed the work as a miracle. It is now placed in S. Maria Novella, between the Chapel of the Strozzi and that of the Bardi of Vernio, where it is still greatly admired by the moderns."

8. Jenkins, Deborah. The Richness of Cities, Comedia & Demos (1997).

9. Calvino, Italo. Invisible Cities, Secker and Warburg (1974).

A case study of the Electric Wharf project is on the ixia website, www.ixia-info.com

© Copyright David Patten 2004. All rights reserved.