How artists can work with design teams on capital projects

An Art Consultant's Perspective

Introduction

Many organisations want to bring an artist into a development project and the role they envisage for the artist varies greatly. Sometimes organisations will want a landmark object to include in a pre-defined niche in the architect's plans; other times they will want the artist to work closely with the design team with the opportunity to have a fundamental influence on the outcome of the development.

Much of the advocacy work of an arts consultant is to try to persuade the clients to be more like the latter. It is always gratifying to see an artist's professional skills accorded the respect they deserve and for their expertise in the field of the sensory impact of a space to be acknowledged.

However, advocacy is only part of the art consultant's job. From the moment the client or the design team decides to include artistic involvement in the project, the art consultant becomes a small but vital cog in the machine that produces a successful outcome. This article not only describes how an artist can collaborate with a design team to achieve the best results, but also attempts to show how the art consultant fits into that collaboration, allowing the design team and the artist to work together to realise and plan for innovative and intriguing outcomes.

The vision thing

More and more design teams have worked with artists before and are aware of the potential for collaborating with them. Many large developers and clients in the private as well as the public sector now have a public art strategy that informs the design team on the parameters (and in some cases the necessity) for including artists in the project.

When considering the potential for an artistic activity within any new project it is advisable to engage an artistic advisor as early as possible into the process. By exploring the potential for the arts at the earliest time, at an early planning stage, an arts programme can be conceived, approved and from then on managed in a way that is most appropriate for the development.

Having a clear understanding of the roles artists will be performing at conception of a project will allow for the funding to be allocated throughout the life of the development. A further benefit is that the potential for the artist can be fully debated, reviewed and adjustments can be made to reflect the often changing nature of a development.

For example, in Bristol the client, The Bristol Alliance, commissioned Hazel Colquhoun and Sam Wilkinson, as arts consultants, to produce a document that outlined a potential art programme. This was approved by the partners and the master-planning architects and then included as an integral part of the detailed planning submission. In doing this they considered a wide programme of artistic activity that embraces a diversity of roles for artists and commits them to a minimum contribution to the art programme. Bristol City Council has a clear picture of the breadth of commitment to the arts and has approved this programme as a significant part of new Bristol Broadmead development. This paper also clearly indicated the mechanisms for artist's appointment and outlined the process and management tools that would be applied throughout the art programme. It is important to say that the programme submitted also allowed for the potential for change. This was vital to ensure the arts could best support and reflect the place and the people that make Bristol and the Broadmead development.

The value proposition

For a client or developer to commit fully to inviting an artist or artists to perform a fundamental role in the design team, they must be convinced of the value of this involvement. In the majority of development projects, at any scale, the capital budgets will be tight and the profitability of projects marginal. It is useful if at the beginning of the process a commitment is made to the arts so its budget is protected and cannot fall victim to cuts and cost plan adjustments later in the programme.

It helps if the client and their team have a sophisticated understanding of the benefits of embracing the ideas of an artist. This understanding must extend beyond the arts adding physical value and contributing to a vibrant and relevant new place. The client should also recognise that a well-planned and effective arts programme can establish vital links into the marketing and the long term sustainability of a development.

A major part of this marketing value is to create opportunities for engagement with communities and those individuals and groups who may not find a voice through formal mechanisms of consultation. This is not to say that artists should be solely responsible for the community consultation work that must take place, but to say that many artists' work is informed and stimulated by experiences, memories and views of others. The dialogues in which the artist engages do not have to be confined to the design team.

There will always be those who struggle to acknowledge this value. A recent conversation with a quantity surveyor for the main contractor on a design and build contract indicated clearly that he had no "truck" with art and would not prioritise the works that a number of artists had developed for the site in question. As this individual was key to integrating the work into the construction programme and releasing contracts to the specialist subcontractors, this attitude could have put the project in jeopardy. This is increasingly important as Design and Build contracts proliferate and as there is more use of PFI in major development. In this case, in my role as arts consultant, I was at least partially successful in changing attitudes by taking time to discuss in more detail the concepts and benefits of the work with the subcontractors, to ensure that they understood the significance of the works in the context of the wider public realm.

A lesson from this experience is to meet and share the benefits of the public art programme with the ever growing team charged with delivery of the project and that this should have been done immediately on their appointment to the project. Advocacy and awareness-raising is an ongoing task throughout a development.

Setting the scene

For the art consultant, a fine balance exists between establishing an understanding of the potential for artistic activity in a project, and specifying opportunities that become too prescriptive.

The arts consultant must be creative; if not, the doors of opportunity could be closed before an artist is invited to the table. On the other hand, this invitation must allow for what artists, architects and designers do, to lead us into places that we cannot plan for in advance.

The complexity lies in raising people's aspirations, trying to give an indication of the type of work that artists may generate without specifying outcomes to the client and the wider team. It is critical that the potential an artist can bring is safeguarded through a process that establishes a clear understanding and rationale for their invitation to be part of the process. The consultant is responsible for ensuring that the scope for the arts programme is realistic and deliverable but also allowing for the unexpected and the remarkable.

Two become one

It was a privilege recently to witness the profound effect an art programme can have on a significant development project. The commission, currently underway with Land Securities and Canterbury City Council at the Whitefriars development in the city centre, offers an interesting example of how an artist can work when fully integrated into a design team. When it works well this can have a beneficial impact on the wider business interests of the development partnership.

For this project, Janet Hodgson was appointed as artist-in-residence to work with the archaeologist exploring the site and the city. Her role was, in the first instance, clearly to explore the site with the archaeologist but also to develop temporary works to encourage debate. Underpinning all her work was a role as a design team member, a role that she was given an unequivocal mandate from Land Securities to perform. Janet has worked for 3 years now in this context and her shared vision with the project architect Catherine Hennessey has remained intact throughout this period.

'Drawing with furniture', drawing for permanent work, Janet Hodgson, 2003

Canterbury

There is one very particular anecdote that exemplifies her impact on the debates about the public realm. The event was a major design team meeting. In attendance were all the key design professionals. The meeting was to report back and review their concepts within their own specialist areas of activity, the architect, the artist, the lighting designer, and the Way Finding and Signage company. The team had all been aware of each other's work before this day and comments and discussion had been on going but at this meeting, decisions for the detailed planning application were being made. Janet took the informal role of "editor", and with the architect encouraged debate among the group about the public realm.

As the debate continued, even though the ostensible subject was Janet's work in the context of the development, the team's perception of the entire public context of the scheme changed noticeably. Artist-led discussion led to a new outlook on the site that had significant practical implications. At the mundane level, the new vision engendered by Janet's session resulted in, amongst other things, a much simplified lighting scheme. But overall the result was a clearer view of the design as a whole and this in turn enabled the whole design team to work together more effectively towards their new common vision.

The Artist

Site-specific work, collaborating with other people, is not appropriate for all artists, nor do all artists want to work in this way. This is a particular discipline that requires management and communication skills as well as their own creative talents.

However, one of the keys to an artist working effectively in the public realm is a willingness to integrate into a team, perhaps relinquishing some sense of autonomy in the process. This includes willingness and the skills to debate their own work and ideas as well as those of others in a professional way. A successful artist working in the public realm must be able and willing to share their ideas and inspirations with individuals and organisations that have little or no idea about artists or artistic activity. This implies a confidence in their own practice and professional skills and an ability to communicate as well as engaging in a shared approach to generating ideas.

On a practical level, the site-specific nature of the work means the artist must address the issues and the diverse contexts in which the work is to be created. This also presupposes an awareness of the timescales that public art and major development project can consume.

The artist must want to develop their artistic practice to work in the public context. Public art commissions and the processes that underpin them are not easy. The reality for an artist is that they must be able to manage complex negotiations about their work in the context of much wider creative debates. The time commitment to a project can be significant. It is often the view that the budgets available for public art commissions and programmes are significant but the work that is required to ensure effective delivery is rarely fully comprehended.

Not all artists want to engage in the process and they must be clear as to what is expected of them at the outset.

New layers of dialogue

An evaluation process on a project in Coventry for a site known as Electric Wharf is currently in progress. This is a regeneration project on the site of the old power station that is adjacent to the Coventry Canal Network. Here David Patten (artist) and Larry Priest (architect) have established a working relationship that has resulted in a ground-breaking degree of collaboration. The achievements on this project are many, as are the number of problems that the team worked through.

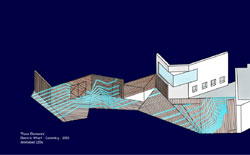

Visual conversation between David Patten and Larry Priest, 2003

Electric Wharf, Coventry

A significant outcome is the fact that the relationship between Larry and David is such that there are no boundaries perceptible in the vision that they have created for the public realm. Their work has formed the bedrock on which other artists have worked. The other artists have created work that offers a range of layers to the development, enhancing the legibility, visibility and understanding of the site. The first artist who joined the team was Charlie Gallagher, a photographer, who researched and documented the site. His work began well before the development started and will be ongoing through to completion.

The project appears to have been incredibly successful in allowing the different skills and roles that artists perform to evolve in a way most appropriate for the development. At no point did the client prescribe any particular outcome, however the team, the artist, architect and art consultant with the client all agreed that an installation that gave a sense of arrival and the night-time presence of the development would be a challenge and an asset to the vision. A simple brief was given to Esther Rolinson (artist) to explore. Her work, a floor based, programmed l.e.d. lighting installation, animates the entrance area and flows through the site and continues to create interest and activity along the entire canal edge of Electric Wharf.

Trace Elements, design drawing for LED lighting system, by Esther Rolinson, 2003.

Electric Wharf, Coventry

Another vital layer to the programme of work for Electric Wharf has been the activities lead by muf, who have accepted a brief, which is in essence to explore and consider the edge of the development. muf 's work has identified communities, old and new, that are affected by the development of Electric Wharf . Their activities and research has sought to capture and understand the impact of change they have also considered the social systems that exist in the area of East Radford in Coventry.

Garden party with children, muf, 2004.

Electric Wharf, Coventry

These layers that celebrate and encourage the different approaches that artists take in their work have been vital to the scheme . David & Larry's partnership has shown that there can be a role for the right artist to integrate thinking across a whole development. What is clear is from our experiences at Electric Wharf is the potential for artists, given the freedom and support, to create a unique, yet unified vision for a development.

Artist supporter

The art consultant's role as a supporter of the artist, in conceptual and practical terms, will vary from one artist to another and from one situation to another, with some needing little ongoing support. With proper briefing and sufficient preparatory work, the support which the majority of artists need from arts consultants can be kept to a manageable level. In general, though, it is constructive and helpful to the entire design team if the art consultant can act as a representative for the artist and protect their interests and 'place' within a project team. For instance the consultant can take part in general discussion on ideas and approach and do research on specialist suppliers and technical advisors (if this is not available within the design team). In addition the consultant will often go to meetings on behalf of the artist where an extensive contribution from the artist is not required, or just as a reporting mechanism.

A major role is to promote the ideas that the artist and the wider team have developed to the outside world; to the planning authority or the wider client partnership, to the wider client team as well as their marketing and PR. This is increasingly important as the benefits of the artist's role and the impact of their work are recognised as a major contributor to corporate social responsibility and public profiling.

Finding the right artists

There are a number of conventions about the way artists are appointed and how ideas are generated, some of which are more or less appropriate for a collaborative approach as outlined here. For many commissions in the past, a number of artists are invited to make proposals from which one is selected to take forward into the development. This is a relevant process for occasions when the proposed work can function to a degree independently from the wider development (although all commissioned work should take into consideration the context).

For the nature of the work that comes through collaboration, some of the key things the consultant is looking for are quality of ideas and approach to developing artworks or interventions. An indicator of this potential can be gauged from the quality of the artist's past work but equally important are their personal skills and ability to integrate themselves into a team. By appointing an artist through informal interview there is a chance for all parties to assess how well they may be able to work together.

On a recent occasion, four artists were interviewed to join a small and already quite established design team. During the interview with one of the artists, it became clear that they would find it difficult to work with a particular architect on the team who had some very clear views on visual arts practice. The architect's views were not negative, I hasten to add, but views that were different to this artist's.

In the end the artist did not feel that that it would be possible to work on the commission if selected. The point of all this is to say that the interview process was designed to allow for just such a possibility and it was much better for this to come out at an early stage rather than after the artist had been appointed. An interview is a two-way street and should be set up to allow all parties to make their views known.

Conclusions

- Collaboration is about shared visions underpinned by robust ideas. A successful project is one that ensures that the vision and ideas are protected throughout the delivery of a development.

- The key to successful projects is to find processes that lead to the appointment of the right artist, so that the greatest potential for effective working is created. The client and developer must be committed to investing in ideas from their entire design team, including the artist.

- The sustainability of an artist's vision and influence throughout the life of a project is an important part of the success of the collaborative process. The outcomes of the collaborative work and how it is integral to the experience of the place must be acknowledged by all the participants. It must infiltrate and be adopted by the whole chain of delivery from the client, including their wider team, the architect, and other design professionals through to the main contractors and key onsite professionals.

- Artists in the public realm may contribute to the understanding, ownership and quality of the environment in a wealth of ways. The styles of collaboration presented above are specific examples ; each project should generate new and unexpected working relationships

- It is important to remember that artistic activity that is temporary, performance-based, multi-disciplinary, about process and is socially engaged is valuable within the context of a development. A diversity of practice that reaches a wide range of communities can be vital in stimulating debate and interest about a development or place. This potential for a diversity of art practice should be considered within development projects.

- All projects are different, all circumstances that have lead to the opportunity for the artist are different, timescales and specific complexities will be different and continue to shift throughout the life of the project.

It is the art consultant's job to keep the project tied together and moving, and every day it is different.

© Copyright Sam Wilkinson 2004

A case study of the Electric Wharf project is on the ixia website, www.ixia-info.com .