Advanced Water Treatment Plant

Location: San Diego, California, USA

Artist: Robert Millar

Overview

The Advanced Water Treatment Plant (AWTP) was a $150 million facility instigated by the City of San Diego Metropolitan Waste Water Department (MWWD) to address the City's chronic need for a sustainable drinking water supply. The purpose of the plant was to re-purify irrigation quality water reclaimed from sewage at the nearby North City Wastewater Reclamation Plant (NCWRP), making it fit for augmenting a raw water supply for the city's drinking water system.

A Design Team of engineers, architect, landscape architect and artist, led by Malcolm Pirnie, Inc., an environmental engineering consulting firm, won the contract. Robert Millar, an artist with considerable experience of public projects, played a pivotal role leading the conceptual/visual design team to an imaginative design concept and architectural proposal which met the operational, economic, educational and aesthetic success criteria agreed for the project.

The resulting design included a legible layout for the process equipment in one long building designed to express the re-purification technology in its form and materials, and to make best use of natural ventilation and light, surrounded by landscapes symbolising the notion of 'truth'. The proposal was a radical departure from the banal, camouflage approach to infrastructure building design used in an adjacent municipal infrastructure project. At the request of the client, an educational tour was incorporated into the building design from the outset.

The AWTP was developed by the team up to 30% design, but for reasons unrelated to the quality and reliability of the technology, or the aesthetics and design concept for the plant, the project was not taken forward.

Background

Without imported water, the landscape of San Diego, in the far south of California, is arid desert. Rainfall is unreliable and droughts of many years in length are common. Meanwhile the inhabited landscape of the region relies heavily on water for pools, green lawns and gardens, as well essential maintenance of life.

The search for a sustainable water supply has been a vital concern of the community since its foundation. San Diego currently has to import about 90% of its water, and with a projected population of almost 1.6 million by 2015, it remains a pressing need. San Diego's MWWD had been active since the 1980s looking at research into reclaiming water from sewage. A number of water treatment plants were built in the City which reclaimed irrigation-quality water from waste water.

In 1995, MWWD proposed an advanced water treatment plant which would pass reclaimed irrigation quality water through a more costly microfiltration and reverse osmosis process, re-purifying it to be recycled into the raw water supply for the city's drinking water system. This became the Advanced Water Treatment Plant project (AWTP).

Public Art Policy in San Diego

In 1992, the City of San Diego adopted a public art policy that promoted artist involvement at the inception of selected City capital projects, with flexibility to negotiate project scope and budgets on a case by case basis. Under this legislation the artist, subcontracted to the prime consultant, was part of the proposing team for any capital contract and his/her contribution was integrated within the scheme. The policy was taken up particularly enthusiastically by Susan Hamilton, Assistant Director of MWWD, a department with a major capital infrastructure requirement ($1.5 billion on above ground facilities in the 1990s).

Initial Stages

In support of the public art policy, Gail Goldman, Director of Public Art at the City's Commission for Arts and Culture at the time, regularly met individually with senior officers of each City department to discuss the potential for artists' involvement in their forward building plans.

At one such meeting in 1995 with Susan Hamilton, they together identified the proposed AWTP as a project where the involvement of an artist would add value. The plant was proposed for a site to the north of the city, separated only by a road from the North City Wastewater Reclamation Plant (NCWRP) which would produce the reclaimed water to be further processed at the AWTP.

MWWD commissioned a Pre-Design Report for the project from Montgomery Watson Engineers which was adopted by the City in April 1996. It set out the processes and equipment required for the purification process, with a proposed site layout with thirteen separate buildings. It also suggested that the AWTP design should be visually linked to the adjacent NCWRP.

The Pre-Design Report formed part of the Request for Proposals sent to engineering firms. Three responses were received, each proposing a full Design Team of process and mechanical engineers, architect, landscape designer and artist.

The interviews were led by MWWD and concentrated solely on the engineering requirements of the contract and the credentials of the lead companies. Gail Goldman prepared interview questions related to the engineer's approach to integrating artists on the design team. She participated in the interviews as a non-voting advisor, commenting on the public art history of the engineers and artists.

The contract was won by Malcolm Pirnie, Inc. (MPI), a large and established environmental consulting firm with 40 offices and a considerable record of successfully delivering complex projects. The contract with MWWD was signed in September 1996.

City Council Aspirations

The pressure on the City Council to find ways to meet San Diego's need for drinking water had guaranteed support in principle for the AWTP project, but commitment to the project was ambivalent. Paul Gagliardo of MWWD had carried out the preliminary research into the engineering technology. His role within the project was to evaluate the implementation of the technology through the design, ensuring the most effective realisation of the design brief. He was also responsible for advocating the project both to the public and within the City Council.

Paul was fired by the project's potential to fulfil multiple objectives: to satisfy the City's clean water needs; to educate the public about and gain their support for unfamiliar, perhaps unacceptable, technological processes; to draw international interest and acclaim to the City. His assertion that the City was looking for a 'World Class' facility both in design and technological terms was an explicit challenge to the MPI Team.

The MPI Team

The project manager for MPI was Doug Owen, an experienced engineer and project manager who had a personal interest in architecture. Whilst MPI had 10 years of experience of working with artists, for Doug himself it was new terrain. MPI had assembled a conceptual/visual design team including a project architect, landscape architect and artist to work with the company's team of specialist engineers and civil designers, mainly from individuals and companies with which MPI had worked in the past.

The conceptual/visual design team included landscape architect Steve Estrada and artist Robert Millar both of whom were familiar to MPI. MPI's first choice of architectural firm was not available. An architecture, planning and engineering firm which had been involved with the design of the administrative building of the adjacent NCWRP was brought onto MPI's team as project architect. The members of the MPI Team met to discuss the project together for the first time after the contract was secured.

Artist's Approach

At that time, the usual approach in San Diego to an infrastructure project such as the AWTP was to disguise its real purpose by housing it in buildings similar to others in the area, screening it with planting and banks or even putting it underground. The nearby NCWRP, although visible to local residents and motorists on the adjacent freeways, was rendered inoffensive by camouflaging it as light industrial buildings.

The assumption by the City, and by MPI at the outset, was that the AWTP would be treated in the same way. The role of the artist in such a scheme would normally be to influence superficial design details, especially in the public areas, and perhaps to create art works to focus and give educational value to an otherwise bland solution.

In spring 1996, Doug Owen rang Robert to tell him that MPI had won the contract. Robert asked him for copies of everything he had regarding the project. He read and re-read the Pre-Design Report and thought about its implications. He became fascinated by the processes which would render reclaimed water pure enough for human consumption - a spectacular transformation which current City design practice would disguise as an anonymous factory.

For Robert, it immediately brought to mind the conflict between what we are taught by tradition is forbidden - drinking dirty water - and what science now makes possible. It conjured the rarely realised promise of technological advance to create a better future, and the representation of California's desert region as a lush oasis. Robert realised that this was a project with huge and exciting implications.

Doug had provided no brief for the artist's role within the project and Robert felt it was open for him to negotiate. He felt it would be most interesting for him to be at the centre of the design of the entire facility. His approach would be to draw philosophical and cultural references into the design process and to question all assumptions. His input would thus imbue the whole design of the scheme, but he would not produce an identifiable art object.

The Art Team

Recognising the skills needed to accomplish this role, Robert knew that he needed an architectural collaborator who would support his role in the project, was strong in understanding and expressing technology within architectural forms and materials, and had the abilities necessary to create and develop concepts quickly. This would complement Robert's own understanding of function, familiarity with engineers, practical experience and ability to deal with volume and light.

As he got to know the members of the MPI conceptual/visual design team, it became clear to him that Doug Owen and landscape architect Steve Estrada (who was a serving member of the San Diego Commission for Arts and Culture and actively wanted to work with artists) would be open to this flexible, questioning approach. However it was Robert's analysis that the project architect would not be prepared to take the creative risks required to produce an outstanding architectural solution.

Robert therefore formally proposed to Doug Owen that the architectural design of the facility should be made his responsibility and that he would staff the endeavour with appropriate designers. Doug turned this down immediately and subsequently rejected Robert's repeated approaches on the same issue. Doug confirmed the remits of each team member, emphasising that the project architect was responsible for the design of the architecture.

However, Doug strongly encouraged Robert to make recommendations to the Team regarding all facets of the project, including the design of the architecture and landscape. He explained that although he would not transfer responsibility of the design, that he would value the artist's input during the design process on any aspect of the facility Robert wished to comment on.

Robert realised the value of this position. He asked for, and received approval, to commission an architectural collaborator to work with him as the "Art Team". Doug was emphatically supportive of this. In December 1996, Robert invited Guthrie+Buresh Architects, whom he knew and respected, to join his Art Team. This series of negotiations gave Robert the freedom to develop an alternative theoretical design for the facility, supported by a full set of architectural drawings, in tandem with the designs produced by the project architects.

Project Concept

In early December 1996, a three day concept design workshop, co-led by Doug Owen and Robert Millar, was attended by the whole MPI Design Team, as well as City staff. The purpose was to develop a joint vision and overall design for the project based upon the campus layout in the Pre-Design Report.

Robert had briefed himself very thoroughly on all aspects of the project. He played a key role in leading and shaping the discussions by querying every aspect of the design as it was considered and took shape, and placing the project issues within a broader architectural and cultural context.

On the first day, success criteria for the project were developed by the different professional groups: operations/maintenance, the client, engineers, architect, landscape architect and artist. These set out a framework for creative discussion and decision on the layout and architectural resolution of the plant.

The following day, the sequence of processes was considered. At the end of the presentation Robert asked why the different processes could not be lined up inside one building in the order that the water would flow through them. This was a dramatic shift away from the Pre-Design Report site plan which proposed a different building for each process. After lengthy discussion, it was clear that using the key criteria of functionality and economics, the 'one building' approach was the winner.

The workshop established the overall shape of the scheme. One 600 foot building orientated from north to south with functions separated over three levels: equipment at ground level, piping and pumps below ground, and an upper visitor gallery - combining an uncluttered overview of the process equipment with safety and operational access. There would be two nodes on the east side for unloading of chemicals, chemical storage and support facilities, direct access at ground level along the east side, and an access road encircling the building for safety vehicles.

The public educational tour, (referred to as the "Didactic Tour" by the Art Team) considered essential by MWWD to help the public feel comfortable with the technology, was mapped out at this early stage. The workshop also identified the issues to be further resolved during the design process.

Design Process

From April 1997, the conceptual/visual design team met weekly for day-long meetings to take forward the design to the required level of detail for presentation first to management within MWWD, and ultimately to the City Council. All members discussed and had the opportunity to contribute to the emerging design proposal.

The Art Team aspired to produce a design which would make visible the technological processes and cultural references implicit in the project. Doug Owen was enthusiastic about this approach which would give a visible profile to the services provided by engineers and scientists which are essential to the survival of their community.

The Art Team was prolific in producing digital designs of their ideas for the evolving architecture, alternative configurations for the storage nodes, methods for controlling natural light, materials and the visitor's visual experience of the public tour route. The project architects needed time to absorb the new approach and ideas they were being asked to take on, and were less active in making a matching contribution.

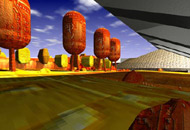

Steve Estrada and the Art Team developed a low maintenance landscape proposal which would complement the layered meaning intrinsic in the building design whilst providing the necessary functional access. A huge prism of excavated waste earth paved with cemented decomposed granite would face visitors entering the site, high at the site entrance and tapering down the west side of the building - a barren landscape symbolising 'absence'. At the end of the public tour, visitors would emerge into a small garden of carefully arranged lush trees, abundant vegetation, rocks and sculpture - illustrating 'excess'.

It is clear from the comments of each participant that the design process was challenging and often tense due to the opposed approaches of the project architect and the Art Team. The former was satisfied by the notion of a warehouse building to provide necessary camouflage, shelter and ventilation for the process equipment. The Art Team was committed to drawing on a broad cultural perspective to produce a project design which would match the international potential of the project.

30% Design Presentation

At the 30% design stage, the project concept, technology, layout, scale, type of structure and suggested materials are presented to the client for approval. By the end of July, each member of the MPI Design Team had produced a report of their proposals for submission to MWWD.

The project architect and the Art Team produced separate architectural visualisations of the building's form and materials. Although both schemes incorporated the site, building, and equipment plan revisions proposed by the Art Team, they were divergent in their further development.

In July, Doug Owen made a formal presentation to the MWWD Management Team of the Art Team's architectural proposal as the plan of MPI's Design Team. It was a bold and inspiring visualisation expressing the re-purification process and meanings associated with the project through every aspect of the design. It was extremely positively received by the Management Team.

In a later meeting with the Management Team, the project architect's sound but unimaginative renderings of the building were compared with the Art Team's visualisations. They attracted little support from MWWD. All documents were then circulated to relevant City staff for comment.

Political Impasse

The project stalled at this point. It was picked up by several politicians and became the focus of debate for political reasons not directly related to the project itself, the safety of the technology, or quality of design. A continuing drought at this point would have made the project essential and it would have continued despite the heated debate surrounding it. Instead the rains fell and filled the reservoirs.

Further Impact

The building design by Robert Millar and Guthrie+Buresh Architects won a Progressive Architecture Citation for Visionary Design, the first time in the forty-five year history of the award that an artist-led design was recognised.

Through this project, Doug Owen's understanding of what contribution an artist could make to an engineering project underwent a huge expansion. At the start, he was well inclined to the involvement of an artist, but had only indirect experience, and that of more traditional object-based artist interventions.

In a subsequent presentation to fellow engineers at the American Water Works Association, Doug reveals his respect and enthusiasm for the Art Team's central role in the conceptualisation and visual design process of the AWTP.

© Copyright Joanna Morland 2003.